Love, Mom: Mother's Day advice from a 98-year-old mom

Which gifts from mom are the real keepers? Daughters and sons, a grandmother, and a mother-to-be help us decide

The best way to honor your mother -- on Mother's Day or any other day? We wanted to figure that out.

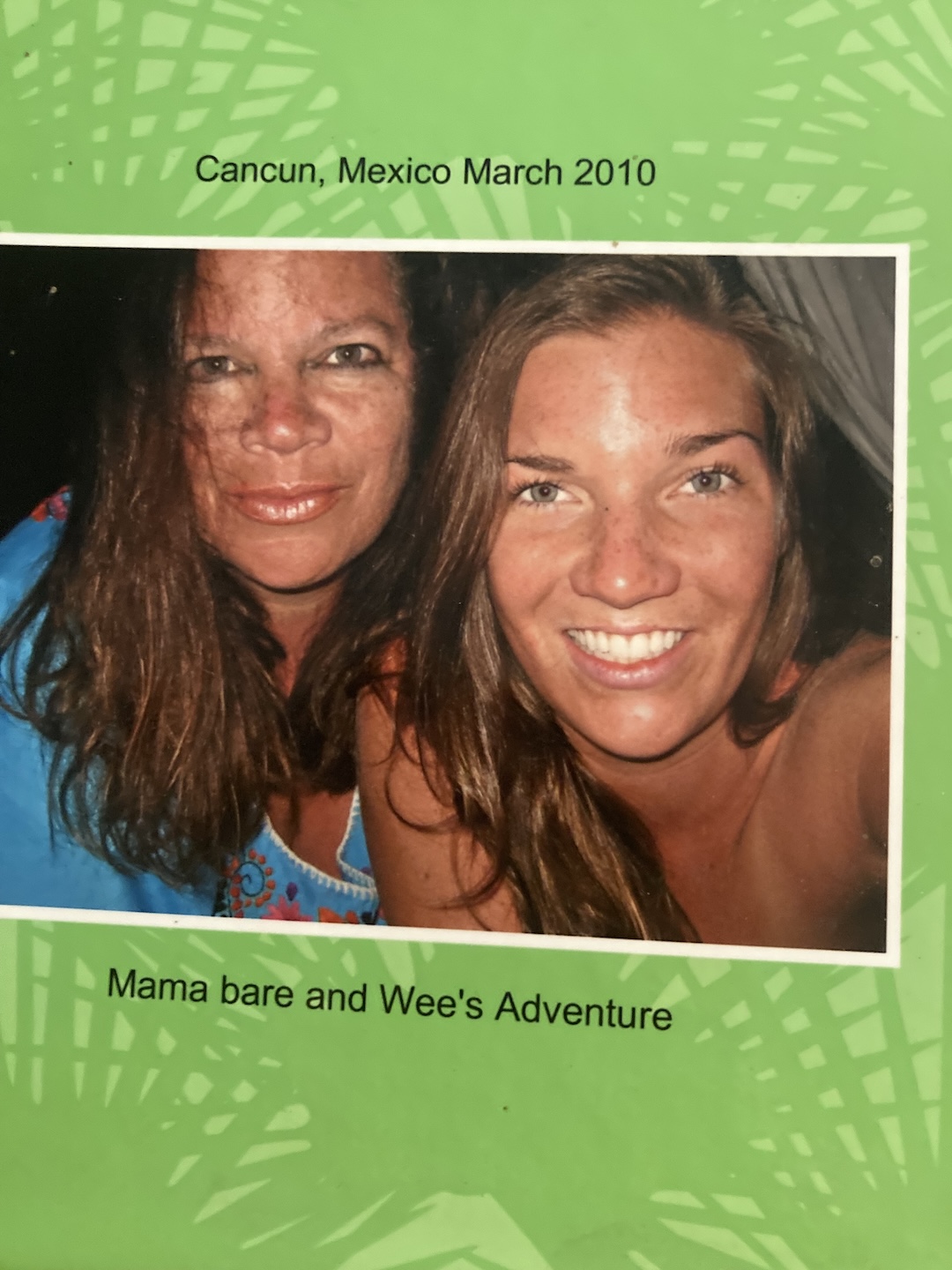

So we got expert advice from family and friends, including Sally's mom 98-year-old Barbara Welsh, Sally's daughter -- mother-to-be Emily Libby. Sally found a photo of both of them about 30 years ago -- and that's what you see above.

As we realized, almost everyone has saved some items from mom. You may not even know what you've got. But when those treasures come out of the attic or the closet, something special happens.

It's a new Mother's Day ritual. Here's some of what we found...

The angel picture frames that Sally got from her mom 25 years ago...

The vase that Sally bought for her mom when she was 10...

The baby blanket from Sally's daughter Emily, which will now go to Emily's baby...

The bowl that Emily made in high school for Sally...

The photo album that Emily gave Sally after a trip to Mexico...

The famous chowder bowl that Michael's mom got for Mother's Day...

All the letters and cards that Michael's mom sent to him...

The still-worn sweaters that Michael's mom knitted for him in the 80s and 90s...

Last but not least, I found this parody of Longfellow's The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, written in 1978 when I was in college.

I saved it all these years. But I never read it carefully even when she sent it to me back in 1978. So I decided to read it now. And much to my surprise... well, you can read it and find out why she wrote it right here.

And that's it for this year. You know you've got your own treasures from mom. If you dig 'em out and put them on Instragram, be sure to copy @throwitoutpod. Happy Mother's Day!

More info, photos, and transcript: throwitoutpodcast.com

Don't miss a thing: Join our mailing list

Do you save stuff you can't throw out? Tell us about it

Want to show support? Please rate/follow us wherever you get your podcasts.

I Couldn't Throw It Out, Season 2, Episode 25

Love, Mom: Mother's Day advice from a 98-year-old mom

Michael Small:

Welcome to an episode of I Couldn't Throw It Out where we address an issue that's close to our hearts. Over the years, some of us have saved items that remind us of our moms. And we need advice about what to do with it. So we asked a mom with a lot of experience. She happens to be 98-years-old. And here's what she told us.

[Recorded interview starts]

Barbara Welsh:

Actually I don't think you can keep enough mementoes. Memory fades in some ways. But if you have a reminder -- a physical reminder -- it helps.

[Recorded interview ends]

Michael Small:

Now that’s a suggestion I love to hear. For more ways that we – and you – can remember and honor our mothers by appreciating the treasures they gave us, keep listening.

[song excerpt begins]

I couldn't throw it out

I had to scream and shout

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

[song excerpt ends]

Michael Small:

Hello, Sally Libby.

Sally Libby:

Hello, Michael Small.

Michael Small:

We have a lot of reason to be happy today because we're about to hit a holiday that honors some people who are really important to us, our mothers. Most people are thinking about their mother in time for Mother's Day. And so we want to share some things about our moms, maybe to get you thinking of the memories of your own mother. For people who save things, and even for people who don't save much, there does seem to be a tendency to save things related to your mother.

Sally Libby:

Yes, because we realize that we're not gonna have them forever.

Michael Small:

What we want to encourage people to do is to think about what they've saved from their mom. And maybe this Mother's Day, get it out, share it, let the world know how great your mom is by talking about the memories that come from the things you saved.

Sally Libby:

Yes, great idea.

Michael Small:

What makes you think of your mother?

Sally Libby:

Beauty. She is just beauty to me, inside and out.

Michael Small:

That's a wonderful thing to feel.

Sally Libby:

Nature's beauty. Flowers spilling out with vibrant colors and a big fat sunflower. My mother would walk into a room and just be sunshine.

Michael Small:

Funny it's all so metaphorical because the first thing I think of with your mother is books and reading.

Sally Libby:

Yes, my mom was a scholar. She read War and Peace twice.

Michael Small:

Wow.

Sally Libby:

Haven't gotten through it once.

Michael Small:

We are unbelievably lucky that your mother is still here. You have given up a lot of your material possessions, but you did somehow hold on to your mother.

Sally Libby:

I did. That was the best possession ever.

Michael Small:

How old is she now?

Sally Libby:

Mom is 98 and she will be 99 years old in July.

Michael Small:

And she was always wise and continues to be wise at this point. So I think we should consider trying to get her on the phone and have her share a little wisdom with us about the things that get saved for Mother's Day.

Sally Libby:

I think that would be wonderful.

Michael Small:

Before we give her a call, maybe we should share a little bit of background about her life. Sally, you want to give us the Wikipedia version?

Sally Libby:

Yes. Well, the short Wikipedia version is that she was born in Mount Vernon, New York in 1925. She studied English at Middlebury in Vermont. At the same time, she was studying my dad, Jackson Welsh, until they got married in 1951. One of her first jobs was answering reader letters for Time Magazine in the 60s. And then in the 70s, she was an English teacher at her high school. And in the 80s and 90s, she was a docent at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Most important of all, considering that it's Mother's Day, she had five children, including me, and she was a wonderful mother to all of us.

Michael Small:

She sure was. I think that's all we need to know before we talk to her and let's see if we can get her on the phone. Okay. We're going to use kind of a crazy rig to call her. So Sally, your audio quality is about to plummet as soon as I patch her in. But here we go. Hello, Barbara Welsh. You are making your podcast debut on I Couldn't Throw It Out. And Sally, why don't you take it from here?

[Interview begins]

Sally Libby:

So, mama?

Barbara Welsh:

Yes, dear.

Sally Libby:

So glad you agreed to speak with us for our special Mother's Day episode.

Barbara Welsh:

Oh my, I have some experience in being a mother.

Sally Libby:

So mom, we want to call on your life experience of 98 years to see if you'll share some wisdom that will help us with our podcast.

Barbara Welsh:

Okay, I'll try.

Sally Libby:

Do you think you can explain why people want to hold on to their possessions?

Barbara Welsh:

Absolutely, because they are fond of them. They like to have the memories of what's happening at that time or what they were doing.

Sally Libby:

Why don't we just throw it all out and live with very little?

Barbara Welsh:

No, I think it's much better to have these memories that come out now and then. And I said, I'd forgotten about that. Yes, I do remember that.

Sally Libby:

Would you say that you're a saver?

Barbara Welsh:

Probably, yes.

Sally Libby:

It was kind of hard for you to throw out or give away things, wasn't it?

Barbara Welsh:

Absolutely.

Sally Libby:

Right. I remember those closets.

Barbara Welsh:

I'm sorry you do.

Sally Libby:

Do you remember anything that you saved that you really loved?

Barbara Welsh:

Absolutely. I saved my dollhouse and brought it with me all the way around the country and it was in our bedroom.

Sally Libby:

It really was exquisite.

Barbara Welsh:

Well, it was probably because it was furnished by my mother and aunt. They loved dolls too.

Sally Libby:

They made incredibly beautiful doll clothes and doll furniture. You had to toss or give away a lot throughout your life.

Barbara Welsh:

I'm a real saver, so it was very hard to do that. It's very, very difficult. In fact, it's agonizing. You often feel like you want to put something off until another time, so you don't have to make a decision.

Sally Libby:

And I think that's what Michael's been doing for about 60 years.

Michael Small:

I always knew I had a strong connection to your mother. We are both savers. And so we have that in common and I didn't realize it.

Barbara Welsh:

I know we had something in common and that was one of those things.

Michael Small:

I remember the Welsh household and definitely there were things saved in basically every corner of that house.

Barbara Welsh:

Yes. Yes. That's true.

Sally Libby:

And sometimes saved with a little bit of kitty pooh pooh.

Barbara Welsh:

Never!

Sally Libby:

I have some things that I'm going to ask you whether I should keep. When I was 13 years old, I was a mother's helper. It was the month of July and your birthday was coming up. So I pedaled 10 miles and I brought you, if I may say so myself, a lovely vase, blue flowers and orange centers. When we were clearing out your house, I took it. It brings back fond memories. I should keep this then, right?

Barbara Welsh:

I should think so.

Sally Libby:

I think so too.Yes. I also have two beautiful frames. They're silver metal and they have wings and a head and a halo over the head. From you, you gave it to me about 25 years ago. Should I keep these two frames, do you think?

Barbara Welsh:

Well, it's quite another use to put inside the frames. Maybe you should double use it again.

Sally Libby:

I really love these frames, so I will keep them.

Barbara Welsh:

Good. I'm glad to hear that.

Sally Libby:

And then one of my favorite photos of you is you're sitting in the wing chair in the living room in a beautiful fuchsia sweater with your black hair flowing all around your beautiful face and you're holding sweet Emily. And Emily was only about, maybe a year. You have such love and joy in your face. And I just love it.

Barbara Welsh:

It's joyful to see that cute little thing.

Sally Libby:

And you cute little thing too.

Barbara Welsh:

Hardly.

Sally Libby:

Yes. We're coming up on Mother's Day. What advice would you give to mothers who are raising children?

Barbara Welsh:

Give them as much freedom as you can bear without having them get into trouble.

Sally Libby:

I love it. I'm all for freedom. Is there a secret to creating a close -knit family like ours?

Barbara Welsh:

I think that anybody who has had experience with a family of her own, relatives and things, will definitely follow that because they will enjoy the feeling of being in a big family, wonderful unit.

Sally Libby:

In a way, you almost have to have the role models, would you say, of having love and compassion?

Barbara Welsh:

Well, I guess it would be, you know? It always follows love and compassion. Yeah. When somebody's been very naughty.

Sally Libby:

But you didn't have any naughty children, did you?

Barbara Welsh:

Never. We only raised the best and we throw the other ones out.

Sally Libby:

OK, here's a question. Looking back, would you have done anything differently as a mother?

Barbara Welsh:

Probably there are a lot of things I would have done differently. And I can't think of any one that one particular one. I would have encouraged everybody to experiment a little more with how they felt and what they wanted to do for having more freedom.

Michael Small:

Sally, I want to break the news to you, which you may not know this, but you are not going to live forever.

Barbara Welsh:

I'm not? I didn't know that.

Michael Small:

I was talking to Sally. We know you're going to live forever. And so if you're not going to live forever, you mentioned some things that you have, like a photo of your mother holding Emily. And I'm wondering, Barbara, what should Sally do with that?

Barbara Welsh:

When Sally has made a decision about whether to throw it out or not?

Michael Small:

Yeah, should she throw it out or is that something that goes to her children?

Barbara Welsh:

No, I would never throw anything like that out because it goes from generation to generation, previous generations don't live forever. So you have a photographic image of something that happened a long time ago.

Sally Libby:

I totally agree with you. And I think that picture will go to Emily for sure.

Barbara Welsh:

I hope so.

Michael Small:

Let's talk about the picture frames with the angels. Maybe that can go to Sally's son, Ben, so that he can.

Barbara Welsh:

Yes, that's right.

Michael Small:

And he can put a picture of Barbara in one and a picture of Sally in the other.

Barbara Welsh:

I think that's a good suggestion.

Sally Libby:

I always tell my mother that my siblings and I won the mother lottery. And coincidentally, we won the father lottery too. We were the luckiest, luckiest kids. And mother too. Mom, you were the best, really.

Barbara Welsh:

Oh I don't know about that. I think there are a lot of other very competent, wonderful mothers out there.

Sally Libby:

I know Michael's mother Doris was wonderful too.

Barbara Welsh:

Yes, she was. I remember so well.

Michael Small:

Doris was wonderful. And I do want to say that we're so lucky that you're here for us to talk with you and we appreciate you so much. So much.

Barbara Welsh:

That's very touching. I'm so grateful for my children and their friends. And all my dears, lovely, pre and post Mother's Day. I'm so grateful that we have such a wonderful family.

Sally Libby:

Thank you, Mom. Love you so much.

[Interview ends]

Michael Small:

Well, that sure was wonderful.

Sally Libby:

Oh yes.

Michael Small:

It was so great to hear your mom. And of course, it really made me think about my mom.

Sally Libby:

Oh.

Michael Small:

The great Doris Rose Levitt Small died in 2018 at the age of 91 after she struggled for many years with diabetes. And I have all these things that remind me of her. I have clothes that my mother gave me, books that my mother gave me, photos, and one of the funniest things I have to remind me of her goes all the way back to Mother's Day probably around 1969. That year, all four of the kids in my family assigned my sister Debbie to buy a present. We gave her all our money, $5. That was a huge sum in those days. So we were expecting something really great. And Debbie went to this old fashioned gift shop called Daniel Lowe's and she came back with this. What is it? Tell people.

Sally Libby:

It's a giant cup and saucer. It has a big yellow flower.

Michael Small:

Well, I'm glad you think it's perfect because we did not.

Sally Libby:

What?

Michael Small:

We were very disappointed that our savings went to that. Debbie came back and we did not respond well and then she was pretty crestfallen. Mother's Day came and we had to present this to my mother. And my mother opens it up. And she says, A chowder bowl, just what I needed.

Sally Libby:

I love it. You couldn't break Debbie's heart.

Michael Small:

The thing is, I always saw this as a great story of how our mother showed her maternal love on Mother's Day and that Debbie had a victory. But I checked with Debbie and she told me she never believed my mother's reaction for a minute. She always thought Doris was laughing when she used that bowl whenever she served gravy or cranberry sauce with it. I didn't see that as a bad thing because Doris loved to laugh. And I thought we were all enjoying the joke together. It was like one of those ongoing family things. But it turns out it's still a painful memory for Debbie. So of course, I'm the one who ended up with the chowder bowl. I had it on display for a while and then I got embarrassed. I put it in the closet and the question is, what do I do with the chowder bowl?

Sally Libby:

I say, give it to Debbie.

Michael Small:

I've tried. She has to check her suitcase carefully every time she visits to make sure this is not in it. I could take it to Goodwill. They probably still pay $5 for it. But because of this history...

Sally Libby:

I know. And Debbie's heart was in the right place.

Michael Small:

Yes. I have to hold onto it and I know that I should take it out of the closet every now and then.

Sally Libby:

Give it a little airing and possibly a little chowder.

Michael Small:

By far the most powerful thing that I say for my mother is this stack right here. It includes every card and letter I ever got from my mother. And there's a lot of them. I just want to show you and get your reaction when you see.

Sally Libby:

Wow.

Michael Small:

Eight inches thick. You know, there's cards. Here's one that says, here's little old me with lots of love for little old you, Dor. Looking at this stack of letters. I think I need to clarify that my mother did not have a realistic view of me at all. How would you describe it?

Sally Libby:

She had you up on the highest pedestal, Mike.

Michael Small:

The truth is she had all her children on a pedestal. I was always hearing her rave about my brother and my two sisters, even though apparently she didn't always remember to rave directly to them. But I think it's possible that I got a little extra in that department. Last year when Mother's Day came around, I wanted to celebrate by reading a few of those cards and letters from that huge stack, and I felt I needed some objective observers. So we asked for some help from our very amazing friends, Jamie and Alison Von Klemperer. And we were really lucky because their daughters, Elizabeth and Caroline, had come home for Mother's Day and they agreed to read letters too. So all four of them came over and joined Cindy and me. By coincidence, my sister Debbie happened to be here too, and that made it a family affair. So now I want to share with you about 15 minutes of what we discussed and how we remembered our mothers.

Sally Libby:

Great. Let's hear it.

[Recorded interview begins]

Michael Small:

Today is Mother's Day and we are thinking about mothers today. And one of the things we sometimes do when we're together is read some things with each other. And I'm asking the family here to help me look at the letters and cards that I received from my mother. Hopefully it'll bring back memories for them about their mothers, which maybe they'll share. And also for anybody listening, maybe memories of what you got from your mother. The big surprise was I did not realize how incredibly loving and generous and kind the notes from my mother were. When we got them, we took them for granted. We kind of read them and threw them aside. But as a whole, when you look at it, it is such a collection of amazing love. And I felt so privileged to see that. I mean, there are people who might say it was a little too much love, but I've selected a few excerpts for people here to read. These are all different ages. One, I was in high school. Most of these I just happened to pull out -- they were from college. And I think since the person who shares the same mother with me as my sister, Debbie, we might start with her. She has a selection here where my mother was writing about her mother, who we called Grammy. Can you explain why she's writing to you and me together? That's why I picked this letter for you.

Debbie Baylin:

Well, I had no idea. You seem to think that we were at camp together and I have no memory of that whatsoever. I was a dishwasher while you were a counselor.

Debbie Baylin:

Okay.

Michael Small:

Would you like to read us this letter?

Debbie Baylin:

Okay. Thursday. That was very typical of mom. Never a date, just Thursday. Dear Deb and Mike, poor Gram is so deaf. I've been screaming for two days. She really can't hear at all, but she's actually been pretty good. For her. Unfortunately, we couldn't go outdoors yesterday. We had a brief outing. I drove her over to the music theater to get a ticket. She couldn't find her panties. And I found them when we got home in her suitcase. So she purchased two pairs of drawers in Marshall's. Just her speed, two for $1. Gram is sitting here chewing a cinnamon bun, which is downright disgusting. So I think I'll end it all and lock myself in the bathroom. Write, eat, sleep, and be grateful for some small favors. I love you both madly, Dor.

Michael Small:

That was letter number one. We're going to move on to Jamie. There was a class, Symbolist Poetry. It's the only time in my entire college career where I actually had the best exam in the class. I wrote to my mom to tell her that I did well on this, and this is what she wrote back.

Jamie Von Klemperer:

So this is written to Michael Monday. Dear Symbolism in Poetry Champ, Boy, am I proud of you. To do the best on an exam is indeed an accomplishment. But what about the hair symbolism in Madame Bovary? Leon curls and uncurls his hair. Emma's first glance is at hair. The stable boy almost swoons when he sees Emma loosen her hair. I was going to have a haircut this week, but now I'm afraid if I do, I'll lose my sex appeal. Now that the pressure's off, how about a letter? Love you muchly. Miss you madly, door.

Debbie Baylin:

My, could a therapist have fun with that?

Michael Small:

Okay, we got to Elizabeth. And Elizabeth is a writer. So I chose, this was the closest I could find for a writer of what she wrote when she went to see a play. And this is her little review.

Elizabeth Von Klemperer:

Okay. Monday. Dear Michael, Saturday we saw California Suite and I had the same reaction I have from all Neil Simon shows. I think Simon considers himself a modern day Shakespeare, thinks he can successfully combine comedy and tragedy. Well, in my book, he can't. I have great difficulty laughing at people in trouble. I did howl a few times, but my overall reaction was, feh. Daddy smiled twice. I counted.

Michael Small:

So there's her literary criticism.

Caroline Von Klemperer:

What a sense of person that comes through these letters. I didn't know anything about your mom, but I feel like I know things about a character.

Michael Small:

That's for sure. She was a character. Let me come around to your reading. Caroline, here, it's this card that I received on my 21st birthday.

Caroline Von Klemperer:

Michael Dear. I usually send you a funny card, but on your 21st I felt I was entitled to a little sentiment. However, I don't have to go into the run of the mill "when I was one and 20" because in your span of years, you've managed to find all the answers and leave me with all the questions. I don't have to utter pearls of wisdom if I had any or offer gems of advice, which you probably wouldn't follow anyway. With both feet on the ground and head in the academic clouds, you've managed to follow a path of dignity, understanding, and humanity, which has compelled those around you to follow with love. This is so beautiful. So have a happy, happy birthday. Have a drink for me. I love you, Dor.

Michael Small:

When you were 21, then you could, you could drink. So that was a reference to being 21. Now, Alison, I brought one for you that is about, being a mom.

Alison Von Klemperer:

Thank you.

Michael Small:

This one didn't have any greeting on it. No hello, no goodbye, but this is what it said.

Alison Von Klemperer:

Your call left me teary -eyed and breathless. Not many parents hear such things said about them. If we have succeeded with you, it was only because the raw material was there. We did our best, made many mistakes, but at least were true to our ideals and moral standards. Thank you for loving us and knowing that we love you. Beautiful.

Michael Small:

And then I got two small ones to read. It says Sunday. And so the days go by, the leaves fall and fall and fall. I've decided there's only one thing less inspiring than doing housework, raking leaves. If only I could discover some use for the end product. But you can't sow leaves, you can't weave leaves. Perhaps I could brew leaves, leaf tea. The whole property is one big mulch. And the most discouraging part about it is to look up and see... leaves. So that was sharing our yard work interests. But then there's one last one. This one I know for sure is from 1975 because it's from the fall I went to college. And it's written sort of like in a poetic kind of format. It says, Dpr wishes to announce that all plants are indoors. All dead leaves are removed. All dead plants are buried. All exposed roots are potted, and after all this, so shall Dor be. You and your big fat green thumb! So she was a character, and you certainly get the loving feeling from these, but we're going to say to Debbie, what's your take?

Cindy Ruskin:

She's shaking her head.

Debbie Baylin:

I'm speechless. These are words that I never heard. I don't want to say it's a mother I didn't know because I knew of her tremendous love. But the expression is so fascinating to me to the different facets of who you are and were then that she's addressing and relating to. I'm intrigued by that and how she positioned each of her children into very different roles. What was always so evident was her phenomenal love for you. It was just all encompassing and she lived through you, I think a little bit. And there were responsibilities that were attached to it, but it was so pervasive and so genuine. I always admired that. So I feel blessed to hear her expression of how she felt about you as your mother.

Michael Small:

Well, thank you. Now, Jamie, one of the things I did not know that we had in common was that both of our mothers were rather fond of us and did not see our flaws quite as much as perhaps other people did. Did you receive correspondence from your mother?

Jamie Von Klemperer:

Yeah, not every day, but pretty regularly because she was an English professor, a college professor. She took great care and pride in her writing. So a lot of her writing was about writing or it was carefully crafted. It was pretty balanced prose. There were too many flights of emotion in my mom's writing. There were kind of analytical letters but they're always meaty, full of visual and other observations of things that most people wouldn't notice. She was pretty astute.

Michael Small:

Did you feel the love?

Jamie Von Klemperer:

Yeah, unconditional and always. Kind of a reliable love. Backstop, always there. The writing didn't get operatic or wasn't highly demonstrative. It was a little bit more rational.

Michael Small:

Alison, as a mom, did you have any reaction, anything you've heard?

Alison Von Klemperer:

What struck by in listening to the letters that were read here was how much your mother communicated two things at the same time, both a love and respect for you, but also that she was sharing intimate details about herself and that she managed to tell you who she was and what interested her and that she was passionate about literature, for example, or your interest in scholarship and academia, or when you were younger, what you might have been doing in summer camp, that she was really interested in you, but at the same time managed to tell you something about her and her interests. I really enjoyed the balance in those letters.

Michael Small:

Wow, that's amazing because I have later letters where her life was not so happy and where she confided in me and told me how unhappy she was.

Jamie Von Klemperer:

That's very unusual. Big parents try to present this bulwark of confidence and not to worry their kids.

Michael Small:

Yeah.

Caroline Von Klemperer:

I don't think it will happen or it happens rarely, but I would want my parents to confide in us the things that are hard. I mean, I guess it's a thing I think about as we get older is just that our relationships with our parents shift. I would hope to be able to have reciprocal relationships where and where if someone is experiencing difficulty or like emotional difficulty, especially maybe in some way that I could be of help as a friend.

Michael Small:

Thank you so much. Was there anything anybody else had on their minds?

Cindy Ruskin:

My mom couldn't be more different than Michael's mom. My mom was very aware of her self -presentation as an adult. And I didn't think of her as funny, but she actually did very funny things and wrote some funny letters. But Michael's mother, the first time I met her, she was watching some kind of game show on TV.

Michael Small:

Name that tune.

Cindy Ruskin:

Name that tune. Then she was jumping up and down on the couch, which my mother would never do either. Because she was so excited because she could name the tune. And she was screaming, turururur. I had never seen anything like this. I mean, I was like, "Is this a mother?" But I did think she was hysterical. She did crack me up.

Debbie Baylin:

You did leave out one small detail there. It was the 10 million dollar answer that she had just won. She carried that with her for many many years. So that was really the jumping.

Michael Small:

I guess anyone thinking... Alison, about your mother?

Alison Von Klemperer:

I guess what was interesting, I mean, all of our mothers, we have to be clear when they were born. So my mother was born in 1922, lived through the Depression and the Second World War. She very much lived in her head insofar as she was great at math and engineering. When the men went to war, she could go into a graduate program in math. So she was given that opportunity. And she was very good at what she did. She read everything she could get her hands on. She led an interesting intellectual life. But the center of her being was being maternal. She was just a deeply maternal and deeply nurturing person who just happened to love to read a lot, but it didn't seem to be in opposition or in conflict. Both of those things lived together happily for her. It wasn't either or. There was no binary for her. It was both.

Michael Small:

Debbie, do you think Doris would be upset that we spent a little while talking about her?

Debbie Baylin:

I pledge the fifth.

Cindy Ruskin:

She's in heaven jumping on the clouds.

Michael Small:

Okay, well, thank you so much, everybody. This is why I couldn't throw out those letters. Now you understand.

[End of recorded interview]

Michael Small:

Okay, Sally, you've heard that my mom was kind of fond of me, in case you'd never realized that before. And I know someone else who's got some fondness and it's you being fond of your two children. One of them worked on the artwork for our podcast. That's your son Ben, and we are forever grateful.

Sally Libby:

Right.

Michael Small:

And one of them is available to talk to us about some things that you saved that she gave you.

Sally Libby:

And it's quite appropriate to have her on this episode because Emily has just informed me that she and Paul are going to be parents in November. Yay, Emily and Paul.

Michael Small:

Let's bring her on to help us with figuring out what you can and can't throw out.

Sally Libby:

Let's do it.

[Interview starts]

Michael Small:

Okay, well, welcome to our special guest, Emily Libby.

Emily Libby:

Hello

Sally Libby:

Emily.

Emily Libby:

Thank you for having me, Michael and Sally.

Michael Small:

Well, we're very excited because we want to talk with you about things that you've saved that relate to your mother and things that she saved that relate to you. Sally, do you want to ask Emily what she's got in her possession?

Sally Libby:

Emily, do you have something that mama has given you that you've kept and you want to keep?

Emily Libby:

Mom, I don't think you're going to be very happy with me. So Michael, as much of a sentimental, emotional, and quite nostalgic person that I am, I also don't collect a lot of things. I try to be quite minimalist, actually. And when I moved across country to San Diego, I did have to leave a lot of things that I normally would probably have with me at home. So. While I do have things that I've saved, they are in a basement somewhere on the East Coast. Dad's basement. However, I will say what I'm most excited about saving from mom is all of the photos that she's taken over the years. And recently she's sent me quite a few baby photos. So it's been really fun to look at newborn pictures from myself. It's just so fun to kind of think about what does our baby gotta look like? I would say the photos, especially digital photos have been the best thing for me to save and to have for nostalgia purposes. But mom, I'm so sorry in terms of actual physical things. I don't know if I really have anything specific.

Michael Small:

I'm just curious. Do you miss saving things? Are you glad you don't have things? Why don't you save things?

Emily Libby:

You know, growing up, I was just very like anal and clean and always like to have things in its place because unfortunately, I just have the type of brain that when there's clutter, I feel cluttered. I feel very overwhelmed. And so I have to have things very organized or else I feel disorganized. But yeah, I would say, Michael, it's really just to keep the peace. As silly as that might sound.

Sally Libby:

To keep your peace of mind.

Emily Libby:

Exactly.

Michael Small:

Knowing your mother as I do, I can assume that you have received hundreds of cards from her.

Emily Libby:

Yes.

Michael Small:

And where are those cards?

Emily Libby:

Gosh. Michael, should I have accepted the invite for this or am I going to be ostracized?

Michael Small:

What you want to say is you enjoyed them so much when you got them.

Sally Libby:

Yes.

Emily Libby:

I do have a box of special cards that I keep. You know, mom is such an incredible writer and there certainly have been cards that, you know, I can't throw it away. I couldn't throw it out. So it's definitely in the box. But like you said, I can't keep hundreds of thousands of cards or else I would go crazy.

Sally Libby:

There's one in the mailbox right now that's being picked up tomorrow for you. Enjoy it for about five seconds.

Emily Libby:

Thank you. That's why I actually don't send cards like for birthdays or Mother's Day. You know, I like to send things that like typically food or items that will be used. I don't really like waste. I really don't. I want to save the environment. It's just so much paper. And I feel so guilty saying this because a card has such beautiful sentiment but I'm too practical for it. I just, it's too much waste for me. I can't, I can't deal with it.

Sally Libby:

That's okay.

Michael Small:

You're a breath of fresh air for this show because I've been a bad example for two years saying I'll throw things out and not throwing them out. And here, I think America wants to thank you for being the person who can show them the correct way to live, which is you don't need all the stuff that I refuse to throw out.

Emily Libby:

I don't think there's a right or wrong here. I really don't. I think it's people preference.

Sally Libby:

I agree. Right.

Michael Small:

I was able to get Sally to admit that she had saved a couple of things that relate to you. And we want to check in with you about what should she do with these things? Do you want to inherit them someday? Should Ben, your brother, inherit them or what else? So Sally, take it away.

Sally Libby:

Okay. Emily has given me quite a few of her ceramic items that she made at her high school. And they are so lovely. I have all of them. And this, this is a waffle woven bowl that's pink and very, very, very light green up here. And it's so beautiful. I love this. What should I do with this?

Emily Libby:

It's beautiful. I remembered that. Well, since you love it so much, why don't you keep it?

Sally Libby:

I will keep it.

Michael Small:

Yes.

Emily Libby:

Yay.

Michael Small:

Do you use it, Sally? Where does it usually?

Sally Libby:

This is a decorative item that goes on the hutch. Well, I could put fruit in it. I have. I've put fruit in it before, yes.

Michael Small:

But it's on display. It's not in a closet or something.

Sally Libby:

That's right. It's on display.

Michael Small:

The Swedish Death Cleaning people said that if it's on display, it's OK. You know, you just don't want it in a closet. Presumably, when it is on display, you go buy it and you think, I have the best daughter on earth over and over and over.

Sally Libby:

I say that every day. Okay. The next item is Emily's childhood blanket. It has a farm motif with fencing, a cow.

Emily Libby:

I remember this. Lambie.

Sally Libby:

And I have actually had it on my bed recently and I just cannot give this away because it's my baby's blanket. So I would like to know, speaking of babies, if you would like this blanket for that baby that's coming in November.

Emily Libby:

100 ,000%, yes. I will take that.

Michael Small:

I'm surprised.

Emily Libby:

I would love to see Baby have Mommy's blanket. I think that would be incredible. Wow, I guess I am changing just from this podcast.

Michael Small:

Yes, but you're going to use it. And that's the key thing. 'Cause people like me just save things without using them. So you're still a model for America. But the time we're done, we can sully you a little bit.

Emily Libby:

Thank you, mom. That's beautiful. I can't believe you saved it.

Sally Libby:

You have made me a few photo books that I absolutely adore. You see this?

Emily Libby:

Yes. I remember our Mexico trip.

Sally Libby:

And this is from 2010. In it, you wrote a beautiful message, if I may read it. And it's Dear Mom... Happy Mother's Day. You are my everything, my rock, my best friend and corny joke teller. I can talk to you about everything and we can do anything together and you make it fun. You have such a warm spirit with the biggest heart. I am so lucky to have a mom like you because you fill me with so much love every day. I love you to the moon and back. Love always, Emily. That's just so wonderful.

Emily Libby:

Thank you, mom.

Michael Small:

Well, I guess that book is definitely being kept.

Emily Libby:

It's definitely being kept, but I can inherit it whenever you're ready. Whenever the next life takes you, I will inherit that.

Sally Libby:

Yes.

Emily Libby:

Jury's still out on the ceramic bowl. We'll see if my kid wants it.

Sally Libby:

Don't let that kid break it.

Michael Small:

Okay. I think this brings us to our last question for Emily on Mother's Day, which is, have you thought at all about your wishes for your child as a mother?

Emily Libby:

I've been thinking about this for a long time. It's kind of scary right now. There's a lot going on. And it's a little bit scary to think about in 18 years when they go out to the job market, you know, how AI will play into it. I don't let that bring me down. I just try to be real about it. What I really care about is just making sure they're a good person, respectful, kind, compassionate. I'm sorry. This is the one thing about being pregnant. I have hormones that are raging.

Sally Libby:

Getting a little emotional.

Emily Libby:

I just want them to be good to others because I think that that helps make the world go round. And I think there are a lot of people out there that are struggling and we don't know what they're going through or they might take their anger out on you. And it's just making sure that my child knows just lead with love and compassion and it will be okay. I know that sounds so corny, but that is what's driving us and making me really excited.

Michael Small:

We spoke earlier to your grandmother and I see in the three of you, in your grandmother, in Sally, and in you, living out the things that you just said. And it's really beautiful.

Emily Libby:

I'm so grateful that you invited me on here.

Michael Small:

It's our honor.

Emily Libby:

Happy Mother's Day. Again, everything that I wrote in the Mexico book is how I feel today. And I love you. And you're going to be an amazing grandma. And it's just going to be so fun to see this next generation. I know it.

Sally Libby:

I can't wait. My two best Mother's Day gifts were Ben and Emily. Love you, love you, love you.

Emily Libby:

Thank you, bye.

[Interview ends]

Michael Small:

Okay, Sally, since it's Mother's Day, I'm gonna tell you, you did a great job raising Emily.

Sally Libby:

Thank you.

Michael Small:

You've done an excellent job of setting an example of not saving things, and she's followed your example, so congratulations on that.

Sally Libby:

Yes, I think that was wise.

Michael Small:

Well, I still have this stack of letters and cards from my mother, and I have not thrown out any of them. Not a lot of progress on that front, although being able to remember my mother and hearing Alison and Jamie remember their mothers and talking to your mother makes us so happy that there's a day called Mother's Day.

Sally Libby:

You said it.

Michael Small:

And I don't think you did much better than I did in terms of throwing things out.

Sally Libby:

No, that sentimentality is just...

Michael Small:

... contagious.

Sally Libby:

When it comes to the kids, I can't.

Michael Small:

Okay, we found your weak spot in terms of saving.

Sally Libby:

That's right.

Michael Small: I'm not pushing anyone to throw things out, but I am pushing people to revisit their memories by looking at the things they've saved. And you get an A plus for that, Sally.

Sally Libby:

All right.

Michael Small:

Anyway, we want to wish Happy Mother's Day to everybody who is celebrating this May and in future Mays. And you can see photos of everything we talked about, the blanket, the chowder bowl, the works. It's all on our website, throwitoutpodcast.com.

Sally Libby:

And we also hope you'll follow us on Instagram at throwitoutpod. Thanks for listening.

Michael Small:

And thanks to the Von Klemperers and Emily and Barbara Welsh and everybody out there who's got a mom. Happy Mother's Day, everybody. Happy Mother's Day.

Sally Libby:

Bye.

Michael Small:

Bye.

Theme song begins]

I Couldn't Throw It Out theme song

Performed by Don Rauf, Boots Kamp and Jen Ayers

Written by Don Rauf and Michael Small

Produced and arranged by Boots Kamp

Look up that stairway

To my big attic

Am I a hoarder

Or am I a fanatic?

Decades of stories

Memories stacked

There is a redolence

Of some irrelevant facts

Well, I couldn't throw it out

I had to scream and shout

It all seems so unjust

But still I know I must

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Oh, I couldn't throw it out

I'll sort through my possessions

In these painful sessions

I guess this is what it's about

The poems, cards and papers

The moldy musty vapors

I just gotta sort it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Oh, I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

[Theme song ends]

END TRANSCRIPT