How Keith Haring Changed Art: Hear Him in '83

His graffiti in NYC subways made him a world-wide art star before his death at 31. Hear my 1983 interview as Haring answers his critics, plus: a chat about Keith with Andy Warhol

(To vote on the Haring treasures I should save, click here.)

Even if you don’t know one artist since Michelangelo, the chances are good that you’ll recognize the creations of Keith Haring. More than 40 years after he started drawing with chalk – for free – in New York City subway stations, it’s still easy to spot his cartoon-like symbols: radiant babies, barking wolves. Now, 35 years after his death in 1990 at age 31 (from complications related to AIDS), his paintings sell for millions, and you’ll see them in museums around the world.

My pal Laura Levine took this photo of Keith at work in the subway for my People Magazine article.

When I interviewed Keith for People Magazine in 1983, he was at a turning point. Major galleries wanted his work. But some high-brow critics called him a self-promoter. They hated the fact that he put his icons on buttons and posters that he gave out for free, and on t-shirts that he sold at his NYC store The Pop Shop. So I pushed Keith to answer back, which he did. I also had a brief phone call with Andy Warhol, who explained to me what he saw in Keith’s work.

When I listen to my interview tapes 41 years later, I don’t feel qualified to explain why Keith Haring’s art still deserves your attention. So I got help from Brad Gooch, author of the authoritative 2024 biography Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. (Both Sally and I loved the book, which was a New York Times bestseller. Highly recommend it.) Brad talked with me about Keith's art and career -- you'll hear his insights just before the highlights from my 1983 interview with Keith.

Haring fans -- you'll love this book.

Of course, there's another reason for this episode: I’ve held onto many treasures related to Keith – and I can't decide what to do with them. This is where I need your help.

I’ve posted pictures of my Haring treasures (like the t-shirt below), along with a poll, asking for your guidance about what to save or toss.

For me, Keith’s art still looks lively and young. I hope you’ll enjoy flipping back in time to hear the energetic 25-year-old tell me about his art, his life, and his dreams.

See my three People Magazine articles about Keith Haring.

Vote in the poll about which Haring treasures I should save.

Have thoughts about this episode? Send us a text

More info, photos, and transcript: throwitoutpodcast.com

Don't miss a thing: Join our mailing list

Do you save stuff you can't throw out? Tell us about it

Want to show support? Please rate/follow us wherever you get your podcasts.

I Couldn't Throw It Out, Season 2, Episode 30

How Keith Haring Changed Art: Hear him in '83

Michael Small

On this episode of I Couldn't Throw It Out, we remember an ambitious and amazingly talented art school dropout. He started by drawing graffiti with chalk in New York City subways and in less than 10 years became one of the best known artists in the world. Back in 1983, I got an opinion about this artist from his friend, Andy Warhol. According to Andy, this artist just takes his marker and he can just do it anywhere and other artists can't do that. Which is exactly what Andy said to me in this ancient phone recording.

[Interview excerpt begins]

Andy Warhol:

He just takes his marker and he can just do it anywhere and other artists can't do that.

[Interview excerpt ends]

Michael Small:

To hear the never shared tapes of my interview with this exceptional artist who you may or may not know by the name Keith Haring, keep listening.

[Song excerpt begins]

I couldn't throw it out

I had to scream and shout

Before I turned to dust I've got to throw it out

[Song excerpt ends]

Michael Small:

Hello, Sally Libby.

Sally Libby:

Hello, Michael Small.

Michael Small:

So guess what? I have right in front of me a pile of things that I've saved since the 1980s.

Sally Libby:

I'm shocked. Shocked, I tell you.

Michael Small:

I doubt that sincerely because you already know I have these things and you know that they're related to one person.

Sally Libby:

Mm-hmm.

Michael Small:

The person behind these objects was so important to the 1980s that I wrote three articles about him in People Magazine, and I still have audio tapes of my first interview with him, which we will hear later.

Sally Libby:

Excellent.

Michael Small:

But first, I'm looking at one of the articles that I ripped out of People. I feel like this is a good place to start. May I read you one paragraph? You may, but just one. Okay then, here we go. This article is from 1983 and it starts like this: When New York City officials decided to paste black paper over expired billboard ads in subway stations, they didn't know what they were starting. On that same black paper, hundreds of white chalk figures began to appear. They took strange and mysterious shapes — a glowing baby, a barking wolf, a cookie-cutter outline of a man with a hole in his stomach. Soon these eerie symbols spread. They appeared on a wall near Manhattan's sleazy Bowery. An exposition in Sao Paulo, Brazil, all over Milan's chichi, Fiorucci clothing store. And yes, this September, even on Farrah Fawcett's plaster cast after she broke her wrist. What did it all mean? Where would they appear next? Okay, so that's how my article began. Sally, it's now 41 years later. Many people have forgotten that Farrah Fawcett was the star of Charlie's Angels. And I think you know the answers to the other questions. Who made those drawings?

Sally Libby:

Those drawings were made by the inimitable Keith Haring.

Michael Small:

Yes, and what happened to his career as an artist?

Sally Libby:

Well, he became extremely famous. His work is so distinctive. Even if you don't know the name Keith Haring, you always know his art when you see it.

Michael Small:

And he produced so much. You know how many of those chalk drawings he did on the subway? Something like 5,000.

Sally Libby:

That's amazing.

Michael Small:

It's one of the largest public art projects in history.

Sally Libby:

How long did that take?

Michael Small:

He spent years on it, like many years. And that was only one of his projects. He was everywhere. He made giant installations at museums, on street corners. He gave away thousands of free buttons and posters. He also opened his own store called the Pop Shop, where he sold clothes and gifts, all with his art printed on them. But at the same time, his works were in galleries selling for thousands of dollars.

Sally Libby:

He was so productive, even though his life was so short.

Michael Small:

Yeah. When he died in 1990, he was only 31. He died of complications from AIDS. I actually wrote a memorial to him at People. And I spoke with many of his friends, including the artist Kenny Scharf, who told me that Keith kept working on his art till his final days.

Sally Libby:

So he never really got to see how successful he'd be.

Michael Small:

He actually was successful before he died, and it happened so quickly. When he first got to New York around 1978, he made a good friend, some unknown singer who called herself Madonna. Just a few years later, both of them were known all around the world. And the respect for Keith as an artist kept growing in recent years. In 2017, one of his works sold for $6.2 million.

Sally Libby:

Whoa, I had no idea that they went for so much. But you can still get his drawings on a t-shirt for $20, right? What a range.

Michael Small:

This raises a lot of questions like how did he get so famous? What is important about his art? And what should I do with this pile of Keith Haring objects that I saved?

Sally Libby:

This is where I get jealous of you, Mike.

Michael Small:

Why? Because you don't have any Keith Haring stuff?

Sally Libby:

No, because you got me to read the really wonderful biography about Keith. I loved it. One of the best biographies I've ever read, really. It's beautifully written. For anyone who wants to read it, it's called Radiant, the Life and Line of Keith Haring.

Michael Small:

And I want to add that it was a New York Times bestseller and it was on the 2024 critics picks list at the Times and the Washington Post. And I still don't know why that made you jealous.

Sally Libby:

I really wanted to talk with Brad Gooch who wrote the book and we were supposed to interview him together but then I got the freaking flu.

Michael Small:

I'm sorry I just couldn't wait for you but if it's any consolation I'm gonna play the interview for you now.

Sally Libby:

Good.

Michael Small:

And the reason I wanted to talk with Brad is so he could add some perspective to my 1983 interview with Keith. And here's what he told me.

Brad Gooch:

If you had to pick the bumper sticker for Keith Haring, it would be art is for everybody. I mean, that was his kind of motto. He was selling in galleries and showing in museums in Europe, but he was always then trying to figure out how to get around that system and to have art that was accessible to everyone. So when he has his first show,at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in 1982, it's covered on the CBS Evening News because he's bringing in a totally different crowd of young street kids. So, you know, there are thousands of people who went to that show.

Michael Small:

Keith wanted his work to be fine art or was he aiming for people who knew nothing about art?

Brad Gooch:

Keith Haring existed in that, that nexus. You know, the "is it fine art?" Is it... what is it? Is it pop art? Is it... what's the difference? When he first did a sculpture show at Leo Castelli Gallery, he insisted the kids come in on the day before, at least, to climb all over the sculptures. So he liked that crossover.

Michael Small:

Is it fair to say that Keith was similar to Andy Warhol, maybe in the way he mixed high art with pop art?

Brad Gooch:

It's interesting the connection between those two. They had a big friendship. But in certain essential ways, their work was different. So I think, you know, with Warhol, he had a kind of serious surface, definitely like a high art surface, but then the content was a soup can. So it was like there was a silly irony going, you know, treating something silly with great seriousness. And Haring did the opposite. I mean, he used this kind of cartoony look and very often is displaying, illustrating, thinking about very serious kind of topics. So these very colorful, bright pastels are used for pieces that are about nuclear proliferation or apartheid or gay liberation or AIDS. He was actually taking on a lot of the serious issues of his time, including the growth of computers and in this look that looked like it was for six-year-olds. So he did the kind of opposite trick.

Michael Small:

When I spoke with him, he mentioned several times that he was offended by what art critics had said about him.

Brad Gooch:

Critical reaction was intense. He was particularly attacked for starting the Pop Shop, which then brought together this issue of that he was a sellout, that he was a commercial artist. Certainly Robert Hughes was the leader of that pack. So he would write about Keith Boring. He said that Haring was a disco decorator. Robert Hughes attacked Warhol in the same way. And when Warhol died, Hughes wrote this sort of obituary. There was this great put down that says he hasn't done any good art since 1966. And Keith actually wrote a letter to the editor about it, irate about this, saying, you know, if I die, please don't give my obituary to Robert Hughes. By that point, death was on his mind.

Michael Small:

During my interview with Keith, I kept coming back again and again. Is your art commercial? Is it real art? Is it fine art? And I was going at that partly because at the office I sat in the Time Life building just a few floors from Time Magazine where Robert Hughes was the art critic. And I felt that A, I wanted to give Keith a chance to respond and B, I had to cover my ass because the managing editor of Time happened to live with the managing editor of People. So if Robert Hughes complained to the head of Time that my Keith Haring story was badly reported, the head of People was going to hear about it.

Brad Gooch:

I was listening to your interview and I could hear Keith's voice. I mean, you weren't the first person who was asking that question. Interestingly, when my book came out, I was surprised a certain number of art writers writing about or reviewing my book, that would be the kind of angle: Keith Haring, brand or art, you know, this kind of question, sellout capitalist? I found it weird or lazy in 2024, when every artist is involved in a smash up or 99 % of them of fashion and art and movies and celebrity and licensing. I mean, all that is understood now to be of a piece, but he continues to be shadowed by this issue, even though he was in museums around the world.

Michael Small:

The Museum of Modern Art in New York never gave him any support.

Brad Gooch:

Right. The curator of painting at MoMA, Ann Temkin, kind of apologized to me for the institution. I mean, they never bought anything of Haring's. They never showed Haring. She was sort of explaining why this was. And she thought that part of it was at that time, this great distinction between high art and everything else. I mean, people couldn't figure out where Haring stood. Just as interestingly, she said to me, she thought that certain radical art takes about 30 years before people can see it for what it is. And that had happened like with Monet's Water Lilies. It was like an alarm clock went off in the 1950s and everyone got it. You know, she said Haring's at about that 30 year mark. It does look different now in our world and is enormously influential.

Michael Small:

Well, he also had a lot of backlash from artists, as you put in the book. Someone threw a brick through a painting on glass that he did in Melbourne.

Brad Gooch:

Right.

Michael Small:

People painted over his mural on the Berlin Wall. We did a story about it in People magazine. I think by the time our story came out, which I had written, I think it had already been covered over. And then on Houston Street, where he did those big murals, people wrote nasty things on that and covered them. And this does not happen to every artist. Why did it happen to him?

Brad Gooch:

These attacks were coming from East Village artists, right? Who were much like him. Someone threw tar and feathers at him. One of these East Village artists when he was on his way into his show at Castelli. You know, Madonna, who came up through the same community, felt that this was envy and jealousy of an obvious kind. When you get into the Berlin Wall, again, kind of jealousy. So it's sort of like Keith Haring did so well that he made the other artists jealous and they like covered it over. So there was a certain amount of that.

Michael Small:

He was claiming a little too much of the canvas.

Brad Gooch:

Yeah. Another aspect of Keith was that his work was usually on the street pretty much respected. The fact that other street artists, graffiti artists weren't like messing with Keith's stuff was an interesting kind of tribute.

Michael Small:

I got so many insights into Keith Haring from your book. And one that sticks with me is a new appreciation for the way he made his art, the way he covered a huge wall in a few hours with a giant painting, like it was some sort of dance.

Brad Gooch:

Yeah, I mean, he was very much a performance artist in that sense. One of the more fascinating things is to watch Keith Haring painting live, there are video tapes of that. When you watch him doing it, you know, that's the greatest exhibit A for his innate talent and genius with drawing. You see him drawing these things and then you realize that he has to have the whole thing in his head, otherwise it wouldn't work. Like he wouldn't know to put that line there, which wouldn't block the other line that's gonna come up there. Like he had it all and then he would just go in this usually from upper left to lower right and execute it. So to watch that is an astonishing sort of performance.

Michael Small:

In the mid 80s, I often ran into Keith at events. He always seemed very calm, sensible, humble. He was open. He talked with me. He didn't treat me like some square from People magazine.

Brad Gooch:

He was an authentically nice guy. He was very human. Everyone has their moments and he could be mean and oblivious and things, but it wasn't his, you know, his M.O. He really was a well-meaning soul.

Michael Small:

But from your book, I saw a different person. I think the word is relentless. Relentless about producing art, relentless about travel, about sex, about drugs.

Brad Gooch:

He was an extraordinary worker and had extraordinary energy. So he worked 22-7. One day in the life of Keith Haring involved getting on a plane with his two friends, smoking a joint on the way to the airport, going to Paris, going to a meeting at the Pompidou where he was gonna be in a show and he had brought a blank canvas with him because he was going to do a work for the show. Then he went to a meeting at the Children's Hospital where he had volunteered, as he often did in this case, to paint the outside several stories tall with a mural. Then he got on a plane. He went to Germany. He went to a factory where they're fabricating sculpture for show in Germany. Gets back on the plane, goes to New York. It was one day and it's interesting to watch it, but it's also exhausting. You have to be Keith Haring to live that.

Michael Small:

I was actually there in person for many of the moments you describe in your book, the clubs, the openings, the promotional event for Keith Haring Absolut vodka.

Brad Gooch:

Right.

Michael Small:

But as I was reading, I kept thinking of that Jackson Brown song where he says, what I was seeing wasn't what was happening at all because I saw that 1980s scene as a lot of creative people having a lot of fun. To me, it seemed kind of idealistic. Like we don't have to be rich because we're so creative and we're having such a good time. And I know people were doing crazy things, but it seemed kind of innocent to me. So when I went to that bathroom at the Area nightclub, I saw the cool people hanging out there. But I was there to pee. And you write that Keith was in that same bathroom having sex with multiple people at the same time. And I just didn't have a clue about the level of excess with sex and drugs and everything you describe.

Brad Gooch:

Well, yeah, I mean, the first part of what you said is true. They did see themselves as having fun and they were fun and they were creative. But Keith was very much part of the golden age of promiscuity, at least in the early years until safe sex came and then he was still a part of it. It was just the safe sex age of promiscuity. He definitely was a sex guy at a moment when that was so much the handshake of the time practically. So they were part of that, but that at that moment was part of having fun, part of a kind of bohemian lifestyle. The issue was that it all kind of cracked in the middle and then things got more serious.

Michael Small:

I know Keith made a joke when I was interviewing him and said, just don't say I'm doing acid all the time. I laughed, but I think he was being serious.

Brad Gooch:

Right. Keith was very stoned sometimes. I mean, he used drugs and he did acid when he was a teenager and it was a great artistic inspiration for him. I mean, he began doing these kind of abstract drawings that were, you know, a very important breakout moment for him. So drugs were part of what he was doing. There is something to me in a lot of the color and the luminosity that has a hallucinatory quality. I think he was interested aesthetically in hallucinogens. So Paradise Garage, Keith would dance, would take ecstasy. He definitely got ideas from that and you see it, the surface in some of the work. So he did do that one, the third eye, like the figure with the three eyes, that did come after a night of dancing on ecstasy. But at the same time, it would be a mistake to see the work as drug-created, because it wasn't.

Michael Small:

It seems like he related to kids sometimes not so much as an adult, but as an equal.

Brad Gooch:

Yeah, he seemed more comfortable with kids than with grownups, generally. Keith at a dinner party -- unless you're talking about his work or something directly engaging to him -- was not a master conversationalist. So kids, then he would go and draw. You know, they would draw, he would draw. This would be at dinner and restaurants and things. He did that with Sean Lennon. You know, children were a demographic that he was appealing to.

Michael Small:

A little bit of Michael Jackson, like was he still a child in some way?

Brad Gooch:

Yeah. He knew Michael Jackson in that paparazzi way. They have their picture taken together. He went to his concert, he went backstage. That was the kind of figure he liked. Peewee Herman was a figure he liked. So there were, you know, certain of these kid-like artists and performers he felt some affinity with.

Michael Small:

I'm now going to share an excerpt of the 1983 interview I did with Keith for People Magazine. I know you've heard millions of Keith Haring interviews, but was there anything that stood out?

Brad Gooch:

Well, the only thing that stood out, which I didn't completely understand, was he was ambivalent at one point about whether he should mention having a boyfriend to you. What did you think that was about? Michael Small:

I thought it was about 1983. It's hard to imagine now, but back then having a boyfriend and being gay was not something you wanted to print everywhere.

Brad Gooch:

And you're probably right. When he was diagnosed with AIDS later in the decade, probably the most memorable move of his in reaction was to do a big interview with Rolling Stone magazine where he came out as a PWA, a person with AIDS. And, you know, he really lays out everything about his gay life and his medical condition and his thoughts about sex and about death. He was brave and bold.

Michael Small:

Do you think Keith's work will have lasting value?

Brad Gooch:

The back story is, he turns out to be a much more serious and earnest artist than you might think from all the dancing figures on all the t-shirts. His vocabulary, the barking dog, the crawling baby, the spaceships that he used to tell stories, helps it to endure, actually. There was a kind of vibrancy to this calligraphy of Keith Haring's.

Michael Small:

So, Sally. That's the interview you missed. Did you hear everything you wanted to hear?

Sally Libby:

I think so. Brad didn't leave one detail unturned.

Michael Small:

I agree. And so now I'm going to play the excerpts from my interview with Keith from 42 years ago. But before I do, I want to just explain a couple of things. I did not record this to be an audio interview. So one of the things that happens is that Keith goes on these long monologues and I didn't try to maybe break in. So really you're listening behind the scenes kind of to what happens for a magazine interview. Our interview actually was close to two hours, which is funny because only about three direct quotes from him made it into my article. But this time I'll be sharing about 30 minutes of our conversation. And there are a few details that I just want to mention for people who don't know. He refers to Peter Max, who was an artist who did kind of psychedelic designs in the 60s and was considered a commercial artist, not a fine artist. He also mentions Andy and Bianca. By that he means Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger, who were interviewing him for Interview Magazine. And last of all, he makes reference to Julian Schnabel, who is a painter who was very popular with highbrow art critics at the time. And with that, I just hope you enjoy hearing this interview between a 25-year-old Keith and a 26-year-old me in his loft at the corner of Houston Street and Broadway in Manhattan. I started by asking him about his drawings on the subway, and here's what he told me.

Keith Haring:

The thing in the subway was that it proved that you don't have to get the seal of approval from the galleries or any sort of authoritative art person for it to be real art. It went there without going through any channels to get there, it was just... I had to do it as graffiti to put it there. Instead of going and trying to get it in a magazine, trying to get it, take slides to a gallery, trying to do any other thing that would eventually maybe get it in public, cutting through all those barriers and putting it there directly.

Michael Small:

Can somebody actually appeal to the person who's looking at it as a sort of skewed cartoon versus someone with a real trained eye towards art who's seeing it in a whole context.

Keith Haring:

So people related to the drawings are lots of different levels. I mean, you can take them as incredible philosophical ideas, or they can just be cartoons. The only reason that it worked like it did is because different people saw different things in it. But no matter what kind of person it was, they all related to it somehow. It didn't matter if it was a wino on the street or if it was a 7-year-old kid. Everyone has ideas about what they're seeing, has some kind of aesthetic appreciation no matter what level it is. People appreciate a well-made thing, a well-cooked meal, appreciate beauty.

Michael Small:

The fear might be that it would be too intellectual for people who like cartoons and too cartoonish for the people who claim to be such intellectuals.

Keith Haring:

The problem is that the idea that it can be and should be appreciated or made for lots of different people in some ways goes more hand-in-hand with the idea of commercial art or the idea of it being an art that can be put on clothes or put on posters or put on record covers and can be purchased by the average individual. In some ways, the whole idea of what I'm doing is much more in keeping with that than the idea of it being separate pieces that cost $10,000 and can only be purchased by a supposed elite audience of supposed intellectuals that understand this thing that they're buying, And the dangerous thing is that, especially in New York, people are really eager to jump on you for that. I have Robert Hughes in Time Magazine calling me Peter Max of the Subway, which is saying that I'm being the other thing and I'm only commercial crap that's selling out. So you really have to ride this thing where is it more important for it to be something that Joe Schmo can buy and wear because he loves it or can have a poster because he wants it in his house and wants to live with it, which is what art is supposed to be, right? I mean, it's supposed to be something that you live with, get inspiration from, make you happy, whatever. That should be available to anybody. But at the same time, if you only do that, then people don't take it seriously enough, or it's still, it's put into the category of it being like Smurfs or something. You know, so like Smurfs don't have any real kind of philosophic or any kind of message or any kind of, or even Peter Max. I mean, I never looked at Peter Max as being anything more than decorative art, really. Never really can make you think about anything so to call me Peter Max of the subway was really an insult.

Michael Small:

Have people come up to and said oh would you like to design sheets and things like that?

Keith Haring:

Yeah, that's what I'm turning down at this point because of that because it is a really... it's a precarious situation. I got asked to do a bag for Bloomingdales. But I didn't think it was very good timing for me to do a bag for Bloomingdales now. Especially in New York because I mean at some point maybe but I didn't think I needed that sort of association. Macy's has offered me to I mean to sell my shirts or sell anything I want really. T-shirts. Do a whole little area in Macy's for my things. But I turned that down too because it's still... It's like, in the Whitney Museum they asked me to do a shirt and I said yes because that... I mean, that's still sort of safe enough. I still think that it's possible that if you do it slowly and if you do it... If I make sure that at the same time that I'm doing these things that I'm getting a foot in museums which is happening. Then when I do make these things, it becomes, it's almost as good as the painting in the museum, or it's like you're not wearing just a t-shirt, you're wearing a thing that has the same kind of quality as the thing that's in the museum, or it has, I mean, so actually a weird thing that has happened in the subways that in some ways has worked against me, because my drawings now in the gallery, same size drawing as a small panel in the subway, is valued at maybe $2,000, $3,000. So that theoretically makes the things, so it's worth three thousand dollars. I mean if you use a knife and if you're really careful they can be removed.

Michael Small:

Are they removing them sometimes?

Keith Haring:

Sometimes, now more than ever. I last week I did, I don't know how many, I did drawings all week long on the subway and I'd go back the next day and some of the best ones had been cut out.

Michael Small:

About how many drawings did you do last week?

Keith Haring:

All told, well at least a hundred but maybe more than that. Because in one day you can do, in one day I do at least 20 or 30 in a day, and last week I did four days.

Michael Small:

Do you think you've done them in the majority of subway stations in Manhattan?

Keith Haring:

No, there's so many black panels now more than ever. I guess the subway advertising must be losing money, which is what means, that's what the black panels means. They don't have enough ads. They've got to put up these empty panels. At this point, from doing it for three years, I have sort of a general route that I know. I do the Bronx a lot actually, because it's along the Manhattan line. And I, again, like the idea that it should be up there as well as downtown. Just, I mean, even though people from uptown come downtown, it's still nice to see that he had the balls to go uptown and do it there too. Yeah, sure. Because I think it means something to people to see up there that's not just, it's not some trendy boy from downtown.

Michael Small:

Does some of the timelessness of being in a museum, is that appealing to you?

Keith Haring:

Well, and especially when I spend so much time still drawing the subway where things will never, they're lost immediately. I mean, it would be nice to have something left after I'm gone. The subway is still my favorite place to draw. And how much it's worth has nothing to do with that at all to me. But at the same time, I think that one of the functions of art is not only to be about now and about ideas, to be something that people can live with, that people have and see every day. So to do that, you have to make some objects and things that will be around for a while. Having a museum just means that lots of people could see it or anybody, instead of it being in a rich collector's house, which is sort of the least interesting of all situations.

Michael Small:

There almost seems in your methods implicit a kind of criticism about the gallery world or whatever. Is that true?

Keith Haring:

One of the main things that I think is that art should be everywhere and that it doesn't really, that it shouldn't be reserved for white spaces with white walls. It shouldn't be reserved for people that can afford it. And it shouldn't be reserved for people that can theoretically understand it. And one of the most interesting things to me is that the artist is dealt with the same, but the context changes and the people looking at it change. Things like the buttons are on kids' sneakers on Avenue D and they're on fur coats of the ladies on 57th Street. So somehow it makes them all come to some common meeting thing, which is just human.

Michael Small:

When I was at your gallery show, you were signing those posters and giving them out for free. Right over across the way was a real painting, not a poster, but I guess they were going for $10,000 or whatever. So if I want to be able to answer anything anybody could say, one might say, well, why the hell are you selling the painting for $10,000? Why not give that away for a lot less money over there?

Keith Haring:

Because the person that's gonna buy a painting is nowhere near and probably never gonna be the person that's gonna buy a piece... I mean, we don't even have to say give it away, but the person that's gonna buy a print or a piece for $40. It's never gonna be the same person. But still, even in keeping with an artist like Julian Schnabel, who is, I guess, supposedly more important than me. But at this point questionably how much more important than me -- whose paintings are $40,000, $50,000 and now went on auction for I don't know how much $70,000, $80,000. I have no interest in them going that high. I held down the price, I hold down the price as much as possible. I mean it's weird, it's a hard thing to try to do. You can't not want money, but I've never really been really greedy about it. Also because of Julian as a role model. Julian was one thing that I never wanted to be.

I never liked Julian and I always, I really hated his pompous attitude about making, thinking he's making important art and thinking it should be worth a lot because it's important. He's really, I mean, he thinks he's really great and he's all right. I mean, it's really an attitude problem. I always didn't want to be that. So now to see people, there's a lot of people that think that I am that already. It's a really hard thing to try to, to prove that you're not that by doing, you try to give things away for free. No matter how I went about it, I would have gotten attacked. So what I don't see is what someone else sees as the way I should have done it. Because I've tried to do it as carefully as possible to not exploit anything. And I can't think of any other way I could have done it more except to refuse to make paintings. That was the one. If I would have kept drawing the subway, only do posters, only do commercial things, and refuse to make paintings so that you don't cater to rich people, that maybe could have been one solution, but then I liked making paintings. And also just then how much longer are you gonna be around? I mean, it would be nice to have something be around when I'm not here.

Michael Small:

You say your lifestyle hasn't changed. What do you do with your money?

Keith Haring:

It's embarrassing. Where it's all going? I've been wasting a lot, like having a car.

Michael Small:

What kind of car do you have?

Keith Haring:

Datsun 280Z, but also things like... I sort of have a network of people that work for me, to help support my friends. My friend that takes photographs for me and has been documenting the subway things for three years. The photos. I pay for the photos. I mean, I have a friend that comes and does my laundry because it helps him and it helps me. I had my house repainted by a friend. My friend who does framing. Just lots of just little things like that and just wasting money, I guess. Good stereo equipment, stuff like that. My boyfriend has really expensive taste and buys a lot of leather clothes.

Michael Small:

I see also a certain amount of discipline in just plain hard work. I mean, in producing a lot of stuff and just being there and really working hard at it.

Keith Haring:

That maybe comes partly from how I grew up. I grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania. I learned that sort of attitude from my parents, I think. I thought I was an artist from the time I was little. The only thing that I was really ever really good at was drawing. I mean, because I wasn't good at sports. So the one thing that I could always do was draw. It was also a way of communicating with other people, of proving something to other people. I mean, at this point, I've met so many people because I can draw. It's a really nice way to meet all kinds of people that I would have never met.

Michael Small:

People give you zillions of reactions, and they're all different. Is there one time that you can think of?

Keith Haring:

I don't know. I really wish that I would have carried a tape recorder with me, because I get the most incredible comments from people. I was doing pregnant ladies in May in the subway. Partly because I had been drawing babies for two years and I'd never drawn a pregnant lady. It's like, of course I should be drawing pregnant ladies. Someone else, a week later, came up to me and said, I love your Mother's Day drawings. I didn't even think of it. That's exactly what they are. That had never crossed my mind.

Michael Small:

It seems to me that, you know, the hip type people, they're all really like anxious to say, I know Keith Haring or I met him or whatever. How does that make you feel?

Keith Haring:

Well, I mean, I spend more time doing autographs or doing drawings for sort of regular people, people that I like to like my work more than those other people. I mean, I don't go to their parties. I don't do all those things that they want you to do, right? I mean, I'm not impressed by it. I don't care. The people that I like to hang out with, I hang out with. So that hasn't really changed me at all. But at the same time, like signing Farrah Fawcett's cast, too. I mean, that was...

Michael Small:

How did that happen that you ended up signing her cast?

Keith Haring:

Well, I'm sure, I guess, because of being friends with Andy. I mean, it happened because I had dinner... Andy and Bianca are gonna do an interview. So we had dinner together and that's who their friends are. So we all went together and went and met them and hung out. And she asked me to sign her cast so I signed it. I did a little drawing. Two guys carrying a little heart.

Michael Small:

That's nice.

Keith Haring:

You know, it's hard not to be semi-impressed by things like that for me because I grew up in the same TV world that everybody else grew up on. I never thought I would meet Farrah Fawcett. More and more I feel completely sympathetic because more people elevate you into this special... It's like they aren't, they're just normal people too. I mean, I'm getting put in that same kind of area and I can relate to it.

Michael Small:

You're not crazy about it, like being elevated that way.

Keith Haring:

Well, it has, of course, has its advantages and disadvantages. I mean, you can't not like it in some ways. You can't not like people liking you. I mean, the best thing about it is being able to make someone happy by doing so little. Right? Someone that's actually happy to meet you and you do nothing. I mean, that's a good feeling. It can't not be a good feeling. I mean, to do a drawing for someone, who would get, like, really excited? Like, in Tokyo, it's freaky, like, little girls, wanting me to kiss them and stuff. Like, do a drawing for me, and then they're like... I mean, it makes you feel really great. Because it takes so little to make someone so happy. So that, I mean, that part's a nice feeling. But there's also... There's a lot of other shit that goes with it, you know, because other people hate me for things like that. I have so much hostility against me just from the little bit of success that I've had.

Michael Small:

Who would be hostile to you?

Keith Haring:

I mean, there's 500,000 artists in New York. There's maybe 1,000 that are making a living from it, maybe not even 1,000. So there's 499,000 people that think that they would like to be in my shoes, but they're not going to be in my shoes. I mean, the reality of it is the art world is very, very small and always has been.

[Interview pauses]

Michael Small:

I want to interrupt with one explanation here. During the interview, Keith showed me one of his many collaborations with a teenage graffiti artist named LA II. These pieces would combine LA II's tag, which is his graffiti signature, with drawings that Keith made all around the tags. Keith talked with me about their collaboration, and he also told me about another aspect of the graffiti influence on his work. He was arrested many times for drawing in the subway. Even though Keith never wrote directly on the walls and he only used chalk, it was still considered illegal to deface public property. And this was a very emotional subject for Keith at that time because of a very well-known case against the police that had just happened. An African-American art student named Michael Stewart, and Keith knew Michael, was arrested for writing graffiti on the subway. And he was so damaged after the arrest that he went into a coma and died 13 days later. The police were never convicted of causing his death, but Keith and many others felt that they were responsible. So here's what Keith told me about his graffiti collaboration and his arrests.

[Interview resumes]

Keith Haring:

One thing that has always attracted me to graffiti in New York was just the tags. Because for me it was very close to eastern calligraphy and to the abstract work I was doing when I was doing spontaneous brush work. Because it was about the line and the sort of connection between your hand and making a very direct mark instead of something that's rendered or pre-drawn or something like that, so it's real immediate and real contact, sort of. So I had always sort of had respect for those tags. I started noticing these LA II tags, like they'd stick out from the rest of things. Where they were put, how they were drawn in, and how many of them were. About three or four months later, I had done a project doing this junior high school on Avenue D. I met LA II there and we sort of became instant friends for some reason. Like we knew each other a long time. I mean, at that point he was 15. I hanging out with him and he'd come to my studio every now and then to smoke pot or hang out. And one time he was at the studio. I had this piece of yellow metal primed that I was going to do a painting on. I told him he could take tags on it if he wanted to. So he took tags all over the whole thing. And it looked really beautiful without me even doing anything. So I just put... I put lines in between to sort of make the whole thing... All together, unified, right? And it looked really great. So I had it hanging in my house. And a week later, this was when I was still selling things out of my studio, this woman psychiatrist came to my studio and that was her favorite thing in the house. So she bought this thing for her office. So that gave me like a little more incentive, right? So we started doing some more things. For me, it also enabled it to obtain a certain amount of authentically urban graffiti mixed in with mine. It gave it that real feeling.

Michael Small:

I feel like you could just do the LA IIs all over that yourself.

Keith Haring:

Yeah, except I can't. See, I can't even tag my name. I don't know. I think it has to do with living somewhere and seeing it from the time you're a baby and having it and then starting to do it when you're eight or nine years old and starting to do it in notebooks and things like that. I don't know, like, I can't, if I write my name, it's not gonna look like a tag. It's really an acquired sort of style of writing that I can't fake. And I didn't wanna fake it. I didn't wanna jump in and be educated, white boy, come steal graffiti ideas. Some people still portray me as that, as like, having gotten the idea from them and then exploited it.

Michael Small:

What makes you different from the graffiti artists?

Keith Haring:

I mean, I knew their work. I definitely had seen their work for two years before I ever did anything myself. There was no way I would have met them unless I had done it. The only reason I met them was because they saw the things. They weren't sure who was doing it. They started finding out, word spread like wildfire.

Michael Small:

You mentioned it about your arrest. Have you been arrested lately?

Keith Haring:

Last week I got caught by undercover detectives. At first the one cop didn't know who I was, right? Then these other two undercover detectives just came over and it was like... Oh, you're kidding. I've been wanting to meet you so long. You can't give this guy a ticket. He's famous. And going off giving them this whole long thing.

Michael Small:

Did they give you a ticket?

Keith Haring:

Well, he got the other cop to rip up the one. They were gonna give me a ticket that meant you had to go to court. He got him to rip that up, and then they wrote me a $10 ticket, which you just have to send in.

Michael Small:

Did you draw some more that day?

Keith Haring:

Oh, yeah, I kept drawing. They let me finish the drawing. They said, you got finished, right? I said, no. They said, well, finish it. What are you waiting for? They told me anytime I'm in the station that if I see them I can't keep going. And then the next day got caught by a different cop. I was surrounded by all these kids when he caught me. I was at 68th Street. It was around the time when school was letting out. So there was about 15, 20, 30 kids hanging around me watching me draw. I wasn't looking out very carefully. And I had a friend with me taking pictures also. So I turned around and it was two cops. And I just started to give these kids buttons. It was a martyr situation where I was being led away by cops and trying to give these kids buttons. But they ended up, did the same thing and gave me a $10 ticket.

Michael Small:

Have you paid a lot of money in tickets over the years?

Keith Haring:

Yeah, but they're only, they're like $10 or $15 fines. When you go to court, sometimes you have to pay more. Once I had a $100 fine, once I had a $60 fine.

Michael Small:

Do think you've paid $500 in tickets?

Keith Haring:

Yeah, I don't know how much we should play this up because I know cops are gonna read People Magazine. That's thing about People Magazine - since everybody reads it. Like so far they haven't reacted like that but the wrong cop or judge could say what he's got 50 tickets and nobody's done anything. But I must have paid 500 dollars worth. The other thing which keeps me from any real weird cop is being white also because I know not only from things cops have said but just things like Michael Stewart that if someone else had been doing the same thing I've been doing, he might not necessarily get away with it. But being squirrely, white, and having glasses, first reaction I would have is, how much bad could this person really do? I mean, I don't threaten them at all in the way I look. One thing that really freaked everyone out was when Michael got killed because they didn't kill him because he was doing graffiti. They killed him because he had dreadlocks. And you know, they cracked his skull. And his ribs were beaten into his lungs, they punctured his lungs.

Michael Small:

Doesn't it make you now want to do it anymore?

Keith Haring:

I am somewhat safe because I do it in the middle of the daytime, I never carry drugs or a marker when I'm doing it. If they catch me with chalk, there's only so mad they can get. I mean, the worst that's happened is I've been locked in the bathroom by a cop. And I've been insulted. Just verbal abuse.

[Interview pauses]

Michael Small:

Another quick note. I'm sharing here a little bit of the behind the scenes negotiations I had with Keith about what he didn't want me to print in the magazine. This is the part of my interview that was most surprising to Brad Gooch. He didn't expect what Keith told me.

[Interview resumes]

Keith Haring:

I don't know if I want to say I have a boyfriend in People Magazine.

Michael Small:

Okay.

Keith Haring:

I mean, I don't know if I want to consciously come out and say this is my boyfriend. I don't want to completely cover it up and say that I don't, but, I don't want to make it so obvious that, that's what I'm...

Michael Small:

But you have to be really clear about what I can say. Anyway.

Keith Haring:

Okay. Well, I don't think you should say I take LSD all day.

Michael Small:

Oh, well, as a matter of fact, that was my opening line and now the story's off.

[Interview pauses]

Michael Small:

One final interruption. This last excerpt was recorded while Keith was looking through his drawings and explaining them to me. So that's what we're referring to as we talk about the pictures.

[Interview resumes]

Michael Small:

Why have you made the decision to repeat the same sorts of images over and over again like the baby or the running person?

Keith Haring:

In some ways that's a lot like, it's like the structure of language and the things, the way things derive meaning is in their use or in their repetition. The whole thing in some ways can be looked at like a language. The images are like, become like a vocabulary and can be combined and recombined in different ways.

Michael Small:

Also, why so much sexual stuff?

Keith Haring:

Somehow it seems like those things are the things that people react to or like the most. Even though there's so much suggestive sex and so much really subtle things going on about sex all the time on television, people don't really come out and deal with it very bluntly, very much. I think, I mean, I think if you're gonna talk about it all the time anyway, or you're gonna use it to sell jeans and use it to fill stories with it on TV over over again, I mean, you might as well deal with it completely out in the open and not have hangups about it.

Michael Small:

What about this drawing? Can you talk about it at all?

Keith Haring:

It's person standing on his head. You can also look at it as he was upside down. It's like the world turned upside down. Most obviously, he's upside down, so there's something off. He's standing on his head and he's not on his feet, it's somehow twisted around. Also, sometimes they're nothing. It doesn't always have to have that kind of thing, which is also really weird because people always, all people...

Michael Small:

They don't want them to be nothing?

Keith Haring:

No, people really want... I think it's really good because it makes them, if they don't want it to be nothing, they have to make it mean something, which is really the place to have them really is to make them thinking or trying to think of something because they all come off as symbols or signs for some other thing.

Michael Small:

Even though some of them, it's just really up in the air what it's a symbol of.

Keith Haring:

A lot of them are up, know, because I don't think artists always know what they're doing, especially when you're producing things at this kind of rate. Like if I was making paintings that took three months to make, I could be held much more responsible for what that image is that I'm making, or should I would be thinking much more about all the ramifications of that image and what that could mean to all these people, blah, blah. But I'm really producing images at the same rate as the world that I'm living in with television and TV and newspapers and all these things that happen that fast. I mean, think it's more important for me to keep, to go with that and to keep taking images and submitting them back out than it is to be completely aware of what each one means. Cause even if you think you're aware of what each one means, you don't really even know really. I mean, I don't think people completely understand what paintings mean even when they think they do.

Michael Small:

Do you do sketches of that before you do it?

Keith Haring:

No, never. So that's another part of this whole thing. So you don't, I would never. Sketches are drawings. I mean, when I do a drawing, it's a drawing. I don't do drawings for drawings. Drawings are, you know, like I never ever, even the big mural on Houston Street, I never do a drawing before. I do it there, I do it on the thing. I mean, the ideal situation if you're making something is to be in a state of total control but total mystery, right? So that you don't really, so that you're really inventing things and really using your imagination. But I still try to use it in a way that it's as much full of surprises for me when I make it as the end result.

Michael Small:

With all these people wanting you, wanting you to paint, do you ever get to the point where you feel like you're just a factory and you're just doing the same painting over? Is that a fear that that might happen?

Keith Haring:

But at this point, being 25 years old and only having really been working on this work for like two years, I don't think I'm at that point yet. I have endless, I mean have a lot of ideas yet to what can happen. As long as the images keep, I keep having new images then I'm not scared of it. I'm at that point right now where I'm making the best things I'll ever make probably. And that's another reason why I work so hard now is because who knows how long it's gonna last or what's gonna happen. How long I'll even last, you know what. So it's really important to me now to do it because it seems, it seems like it's real and it seems like, like I should just keep, you know, go with the flow.

[End of interview]

Michael Small:

That's my interview with Keith Haring.

Sally Libby:

Oh, so cool.

Michael Small:

It kind of gives me a shiver when he asks how long his art will last or how long he will last. The interview was about six years before he died of complications from AIDS, but it seems he kind of had a sense of what was coming. Three times he talked to me about wanting to create something permanent that would survive his death. After I spoke with him, I called Andy Warhol on the phone to talk about Keith's art, to get a quote for my article. Andy didn't say a lot, but he surprised me with the angle he took. Then we chatted a little, and I assume you want to hear it, Sally?

Sally Libby:

I certainly would.

Michael Small:

OK, here goes.

[Phone interview begins.]

Michael Small:

The one thing that... people talk about the directness or the way it can be interpreted on various levels. Is anything like that part of the appeal for you?

Andy Warhol:

No, I just... Well, actually, my whole reason for liking these kids is because they can actually go travel to a country and do their work there. And that's the best part about their whole attitude and look and everything like that. They can go to South America and they don't have to bring in their work. They can just do it there. They can go to Japan. He went to Fiorucci's in Milan and just painted right there. He just takes a marker and he can just do it anywhere. Other artists can't do that. That's the best thing about that group of people, carry it in their bags.

Michael Small:

He told me about that Fiorucci party. You were there right?

Andy Warhol:

No, no, we were in Milan at the same time.

Michael Small:

Yeah, he said that was fantastic.

Andy Warhol:

He said, now you're here, they tore off the doors and everything, they're selling it as fine art.

Michael Small:

Thank you very much. I'm sorry to...

Andy Warhol:

Oh, it's okay. How's everything?

Michael Small:

Incredibly busy, more than ever, but really fun. I'm just, you know, I got to talk to Jennifer Beals.

Andy Warhol:

You did? Why did they all dislike her?

[End of interview]

Michael Small:

And that's when I cut off the recorder, so history will never know what we said about Jennifer Beals. It kind of seems that Andy liked to gossip more than he liked to talk about other artists. So those are highlights from my tapes. And now we get to the moment of truth. What should I do with the many Keith Haring treasures I've saved? I'm not just procrastinating, but all of these objects are very visual and it's going to be frustrating to hear us talk about them without showing them. So I'm switching things up a little for this episode. I'm going to make a slideshow where I'll include photos of all my Haring treasures and then I'll add a poll where I hope people will tell me that I should keep everything.

Sally Libby:

The goal of this whole project is to jettison some of this stuff. When are you going to cross over that line?

Michael Small:

Well, I might change my ways based on what everyone tells me when they see my stuff in the slideshow. Everyone please weigh in. You can see it and vote on the Keith Haring page of our website at throwitoutpodcast.com. But Sally, I can't bring myself to wait to show you one treasure that means more to me than almost anything from my years as a reporter. I want to show it to you right now, okay?

Sally Libby:

Okay.

Michael Small:

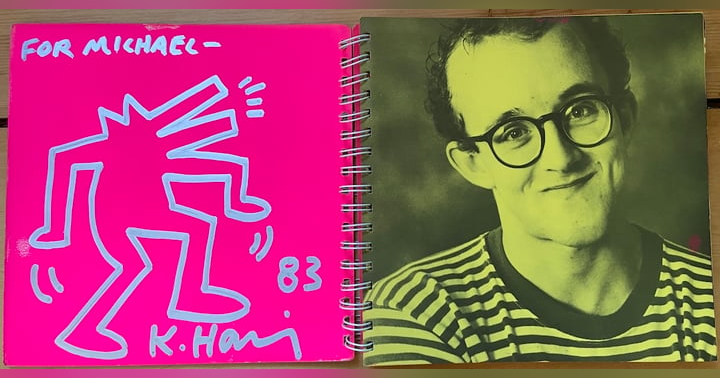

It's a catalog from one of Keith's shows. It's neon pink on the outside with a drawing of a three-eyed man on the front. And on the inside cover, it says, For Michael. And below that, Keith drew me a barking dog and signed it. He gave me an original signed Keith Haring drawing.

Sally Libby:

Definitely would keep that. That's so sweet.

Michael Small:

But Keith signed a lot of things for a lot of people.

Sally Libby:

Right, but just because he signed a lot doesn't mean it's any less valuable for you. Did you check with Brad Gooch to find out what he thinks you should do with your stuff?

Michael Small:

I did ask him and he told me he wasn't good at appraising the value, but he did write me an email that said, listen to this: I think all the items of yours should definitely be cherished.

Bottom line, don't throw them away.

Sally Libby:

Oh, Brad, I'm so disappointed with him. He's an enabler.

Michael Small:

He's my kind of enabler. I have to say that I really enjoyed sorting through my Keith Haring stuff again. So this is just more encouragement to everyone out there. If you've saved things from the past, get it out and look at it. You'll enjoy it.

Sally Libby:

And here's to Keith Haring for all he accomplished.

Michael Small:

And here's to Brad Gooch for being so helpful to us and for writing Radiant, The Life and Line of Keith Haring, available at your local bookstore. Sally, anything else to add?

Sally Libby:

Well, I do have one important note. We signed up for the new social media site, Blue Sky, but we haven't found our friends there. So please find us and follow us. Our Blue Sky name is throwitoutpod. And if you're feeling disappointed with other social media, it's really easy to sign up for Blue Sky at BSKY.app.

Michael Small:

And on our Blue Sky account at throwitoutpod, you'll also find the photos of my treasures, or you can find them on Facebook and Instagram at throwitoutpod. And not to repeat myself, but the photos are also on our website at throwitoutpodcast.com.

Sally Libby:

That wraps it up. Michael, I want that signed barking dog drawing.

Michael Small:

No way. You've got a real-life barking dog at home. Go sweep up the dog hair, Sally. Bye, Sal.

Sally Libby:

Bye, Mike.

[Theme song begins]

I Couldn't Throw It Out theme song

Performed by Don Rauf, Boots Kamp and Jen Ayers

Written by Don Rauf and Michael Small

Produced and arranged by Boots Kamp

Look up that stairway

To my big attic

Am I a hoarder

Or am I a fanatic?

Decades of stories

Memories stacked

There is a redolence

Of some irrelevant facts

Well, I couldn't throw it out

I had to scream and shout

It all seems so unjust

But still I know I must

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Oh, I couldn't throw it out

I'll sort through my possessions

In these painful sessions

I guess this is what it's about

The poems, cards and papers

The moldy musty vapors

I just gotta sort it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Well I couldn't throw it out

Oh, I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

[Theme song ends]

END TRANSCRIPT

Brad Gooch is a poet, novelist, and biographer, whose latest book is Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, published by Harper/Harper Collins in 2024. His previous books include: Rumi's Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love; Smash Cut: A Memoir of Howard & Art & The 70s and the 80s; Flannery: A Life of Flannery O'Connor, which was a National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and a New York Times bestseller; City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O'Hara. He also wrote Godtalk: Travels in Spiritual America, and three novels -- Scary Kisses, The Golden Age of Promiscuity, Zombie00. His collection of stories, Jailbait and other Stories, was chosen by Donald Barthelme for a Writer's Choice Award. He's also a poet; his poems have been collected in two volumes -- The Daily News; and Finding the Boyfriend Within and Dating the Greek Gods. Brad's work has been featured in numerous magazines including: The New Republic, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, New York Magazine, Travel and Leisure, Partisan Review,The Paris Review, The Los Angeles Times Book Review, Art Forum, Harper's Bazaar, The Nation, and The Daily Beast. A Guggenheim fellow in Biography, he has received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship, and a Furthermore grant in publishing from the J.M. Kaplan Fund. He lives in New York City.