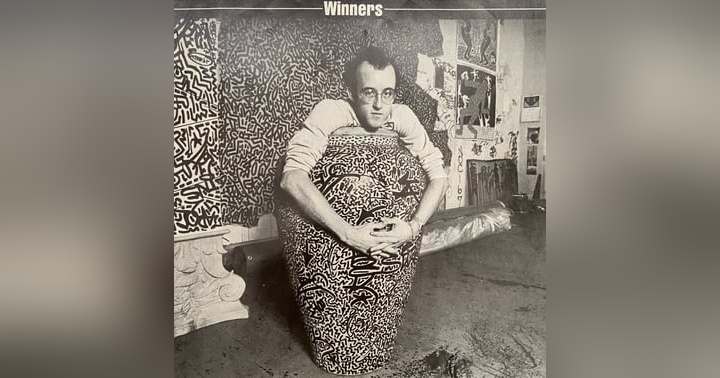

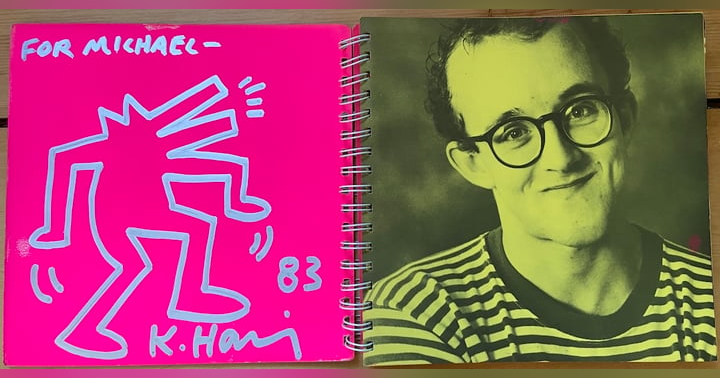

1996 Flashback: My first They Might Be Giants interview

Flashback – November, 20 1996. That's the date when They Might Be Giants' John Flansburgh joined me for one of the very first live-streaming interviews on the Internet. These days, we take it for granted that we can talk in real-time on our computers. But back then, hearing John's voice live through a computer seemed truly futuristic.

In my job as the arts and entertainment editor of the San Francisco-based website HotWired (part of Wired Magazine), I already had been the host of two Internet interviews. One was with musician Laurie Anderson, the other with Yoko Ono. Both of these guests were amazingly articulate, sharing sophisticated ideas -- I could barely keep up. Though I usually save lots of documentation, I had been told that Internet content would be around for eternity. So this time, I didn't save a thing. Not a note. Not a recording.

Then... a few years later, HotWired was removed from the Internet. Entirely. Gone. With it went every trace of those first two live interviews. So much for eternity.

When I was getting ready for the second season of I Couldn't Throw It Out, I dug through the treasures I've saved for decades and pulled out everything I had about They Might Be Giants. One of the things I found was an audio tape of my third live-streamed HotWired interview -- with John Flansburgh. As far as I know, it's the only live interview that survived.

John -- who was about to perform at San Franscisco's Warfield Theater that night -- answered my questions and those submitted by listeners in a chat room. Back then, almost no one had high-speed Internet, capable of streaming live audio. So as far as I could tell, there were about 15 people listening and posting questions. Most of them seemed to be the website's staff members, listening from across the room.

At first, I was hesitant about sharing an interview that's so old and potentially outdated. But then I realized -- it's a time capsule, a snapshot of exactly what John Flansburgh was thinking on November 20, 1996. Though 2Pac, Snoop Dogg and Jay-Z were making music at the time, rap was not yet mainstream. But, during our interview, John accurately predicted that rap would become the most popular music genre. He also shared both his hesitation about the Internet and his prediction that the Internet would help people get unprecedented access to pop culture. He ain't just a Giant, he's a fortune teller!

This year, when I interviewed John for I Couldn't Throw It Out, I had no idea that a few of the questions I asked him were identical to questions I asked back in 1996. I also discovered that his responses were really similar to the answers he gave 1996. So, on the positive side, both of us are consistent. (Hear the brand-new 2023 interview here.)

Anyway, back in time we go. Hear the complete unedited 1996 audio-only interview by clicking the Youtube video below. Full transcript follows.

Transcript: 1996 Live Streamed Interview with They Might Be Giants' John Flansburgh on Hotwired.com

Michael Small:

Hello! This is Michael Small, host of the podcast I Couldn't Throw It Out, bringing you a flashback to November 20, 1996. You're about to hear one of the very first live streaming interviews on the Internet. It's my one-hour conversation with John Flansburgh, co-founder of the rock band They Might Be Giants. We were broadcast live on the HotWired website, which – by the way -- no longer exists on the Internet. So it's just lucky that I saved the complete unedited interview from nearly 30 years ago. If you want to hear something a little more timely, you'll find my brand-new interview with John Flansburgh on the podcast I Couldn't Throw It Out wherever you get podcasts (except Spotify), or at throwitoutpodcast.com. Now here we go. Back to 1996.

Lenny, HotWired:

Thanks for logging on to Pop Talk. It's HotWired's forum for live interactive audio programs. While you're listening to live broadcasts and RealAudio, you can join the rest of the audience in talk.com for a simulcast chat session. That's where you can participate in today's show. Just follow the links that say "Chat here now." And here's our host, Pop Editor, Michael Small.

Michael Small:

Thanks, Lenny. I'm here with John Flansburgh, who is one of the two main members of the group, They Might Be Giants.

John Flansburgh:

The lower half of They Might Be Giants, I like to think of myself.

Michael Small:

And he's in town, in San Francisco for a show at the Warfield tonight and to play a lot of songs from the band's sixth full-length album Factory Showroom, which is perhaps the greatest album by They Might Be Giants and anyone in the history of the world,

John Flansburgh:

Wow. Interesting perspective. But I agree.

Michael Small:

I try not to be biased when I do an interview. Also I would like to add right from the start that uh... John also worked on a solo project called MonoPuff, which was a record that came out...

John Flansburgh:

It came out this last summer on Rykodisc.

Michael Small:

And as I told him earlier, that record is totally rockin', as you will discover when you listen to the song Totally Rockin', which is one of the greatest songs in the history of the world, I believe.

John Flansburgh:

Alright. Now I don't understand why you didn't get along with Yoko Ono. If you start off an interview like this, you're...

Michael Small:

I don't know. That Yoko Ono, she's a tough interview. But we can get beyond those things.

John Flansburgh:

Okay.

Michael Small:

And meanwhile, why did you kill your mother?

John Flansburgh:

Well, she was bugging' me.

Michael Small:

Okay, good answer. I think I'd like to start by asking you about the song, I Can Hear You, on the new record. Would you be willing to tell the folks at home how this song was recorded, why it was recorded that way, and how it all came about?

John Flansburgh:

Sure. Well, actually, a few years ago, it's kind of a convoluted tale, and I'll try to make it as brief as possible. Basically, a friend of ours, Nick Hill, who works at a radio station called WFMU, in West Orange, New Jersey, invited us to contribute a song to this FMU benefit record that was about Thomas Edison. Thomas Edison's laboratory is in West Orange. And so there are a lot of things that sort of celebrate Edison in that town. And there's also... on this truly alternative radio station, WFMU, they have a wax cylinder and 78, sort of a pre-electrical recording show where they play all these old records from the '20s and the whatever you call the O's, the aughts. And then, you know, the 1890s and uh... the people who put that show together have a demonstration at the Edison Museum every year where they bring in some live music performers and they actually cut some wax cylinders and uh... there's this guy named Peter Dill which is an engineer who basically maintains this crazy interesting archaic equipment. He makes his own wax cylinders and this stuff is... basically the wax cylinder recorder is a different format. It's just like a record player in that it's got a groove and a needle and all that stuff and spins around. But what's different about wax cylinder recorders than modern records is that they don't use electricity to work. They're basically just these contraptions that work with sound pressure. And you sing into these... to make the wax cylinder recording, you sing into these giant cones that look like the things that are on your dog's head when you take them to the vet, you know, those things. And one of them is like 12 feet long and one of them is just kind of like, you know, dog-sized. And I sang the song and basically it was like bellowing into this thing and the band was playing into this other 12-foot long one. And it was just a really interesting experience, you know, and to make the recording and to have the, you know, to be in that place and then put the wax cylinder... onto the player and hear it back. It really was like being... I really felt like I was experiencing time travel because there are all these aspects to the way it sounds that really are very specific to that technology. I mean, you actually have to change your performance style to make it work because you have to sing very, very loudly. So there's this strident thing going on that, you know, it's not too different than the sound of RealAudio coming over your computer. But when you hear the 78s and the guy's going like, (loudly) "I love you..." it's not simply because that was the style of singing that was popular at the time. It was also that they had to sing very loud to be heard. That was the big revelation of the whole experience was that there was this technological part of making those recordings back then. So we were flattered to be invited. I guess Wynton Marsalis had done it the year before and Les Paul had done it the year before that. Les Paul wouldn't play an acoustic guitar, which I thought was kind of cool. He stuck by his electric. He's like making a recording on this wax cylinder and he still had to play electric.

Michael Small:

I keep thinking that after Armageddon when there's no more electricity the only music that will survive is like this song. People will be listening to this over and over and over again.

John Flansburgh:

Well, the song itself is a site-specific song. It was written for the performance. For people who aren't familiar with the song, basically it's kind of all the different things that you hear coming out of speakers. The wax cylinder was the original mechanical sound reproduction device. It wasn't just the first record player. It was also the first speaker. So that's what kind of set my imagination going, thinking about how it's affected our lives and how many things have little crummy speakers making noise at us... Especially living in New York. I guess it's probably true everywhere now just between phone machines and intercoms and...

Michael Small:

Computers.

John Flansburgh:

And computers. And car alarms. There are all these car alarms in my neighborhood that like talk at you now, that are just kind of strange and distracting. So that's what the song is about.

Michael Small:

Another song I wanted to talk about is "Spiraling Shape." I find the song really interesting. For people who haven't heard it yet. I guess it's about the latest trend and the need for a new trend every other minute or something like that.

John Flansburgh:

Well, it was originally... it was written to be in this movie for The Kids in the Hall, The Kids in the Hall movie. I don't know what it was finally entitled. I think the original title was The Drug. So it's kind of got a drug aspect to it. About the psychedelic experience.

Michael Smal:

But isn't it also about how trends come and go, which is what I read in the liner notes?

John Flansburgh:

Right, right. Yeah, I guess, I mean, that would be a much better question for my partner, John Linnell, who really, who's the author of the song. So I don't want to put words in his mouth. I don't know, it's hard for me to completely grasp what the song is about.

Michael Small:

Your career has extended over so many years and you've seen so many trends come and go that I wanted to ask you about a few of the recent trends that this song might refer to. For instance, have you kept up with cocktail music and do you have any opinion about the whole lounge scene?

John Flansburgh:

Well it's interesting because friends of mine were really a big part of... Bar None, our original indy label back in that eighties uh... out of Hoboken New Jersey uh... put out the first Esquivil reissue. I guess it's kind of like the beginning of uh... and that was the big original lounge music reissue uh... I don't know, I think American culture has figured out camp at this point which is kind of interesting. It's strange to me to see mall culture become campy you know as opposed to kitschy.

Michael Small:

I have trouble thinking of any truly sincere and deeply heartfelt music that's cool. It seems like in the sixties this very heartfelt music was cool. In fact there's even a reference in one of your songs to-- "letting my freak flag fly.' Do you get the same feeling that sincerity is not particularly popular at the moment? Or do you think that's...

John Flansburgh:

Well, that's a really interesting question. For me, I feel like sincerity is something that you can't just declare. I mean, I feel like it's kind of an unsophisticated point of view to just say, "But I'm being sincere." That doesn't necessarily... most things are essentially sincere and most people are essentially sincere. But they're not really necessarily operating... It's more complicated, I mean the world is more complicated than simply being sincere and it doesn't mean much to be sincere.

Michael Small:

How might that applied to your music? You know one of the things I read about They Might Be Giants that annoys me is that people write, "They're too clever for their own good." And I always think, "Well, what is too clever?"

John Flansburgh:

Well, a lot of people are looking for music to take them away from their day-to-day concerns and so obviously if something is very streamlined and simplified that's a very easy vehicle that people can jump on and find themselves going to whatever place that that music... you know, that's the function of... whether it's like rootsy R&B, like sex music, or if it's new age music. In a certain way, the way people -- it seems like a lot of audiences -- experience music is this kind of escapist kind of thing, and I think what probably bugs a lot of people about our music is that it's this very complicated thing that draws on a lot of different uh... there's this kind of uh... well it's hard to describe exactly. But a lot of times by the time we get to the third verse we'll actually draw something in that will make it almost impossible to stay within the song. We almost kind of destroy the mood of a song in this purposeful way and it's not an active uh... we're not trying to be contrarians. We're not trying to like ruin the vibe. But I think it's just there's something about what we're doing that we really want to experiment with the form of popular music and I think everyone's very familiar with music that just sets the mood and sticks to it uh... So you know, people say we're irritating, I mean that's probably true. We probably do irritate a lot of people. But for me personally I find a lot of people really boring. So maybe it's an even trade. Yeah, well, a lot of music and a lot of audiences. I mean, I can't believe what people choose to listen to in their spare time.

Michael Small:

Are you willing to go ahead and spell out a few of the things that you're not particularly crazy about?

John Flansburgh:

Oh, you know, virtually anything. I mean, I'm just like anybody else. You know, I go into the record store, I'm like looking around going, "Man, I hate all that." You know, it's like, "Where's the good stuff?" People are always kind of down on... I mean it's interesting for me because I don't hold it against music. Unlike when I go into the video store, I'll go, "I don't really like movies. I don't like the movies. It's very hard for me to find a movie that I'm interested in." Whereas other people I know, they're just movie fans. They're happy to consume movies, even though they just might even feel like they're kind of worthless.

Michael Small:

You said that you do some unconventional things with the music but it's interesting because you actually use very conventional pop music also and you sort of mix experimental with pop music.

John Flansburgh:

Right. I don't think that our music is experimental in the sense that, you know, like John Cage is experimental. I wouldn't want to, like, I do know the difference. I mean we're... working in this pop form and it's a very strangely orthodox kind of uh... world that we're working in. But I think that there is this sort of open invitation in pop music to bring in elements that will make it completely different. You don't have to do too much to break the form and still be kind of doing something that's quite different than your average top 40 music.

Michael Small:

Well, we have a lot of questions coming in from people who are listening and chatting. And you can actually select a question over there and go ahead and answer it.

John Flansburgh:

I'll just read them off. Is that all the way from the top? "How do they get off with minimal drums? I noticed on 'Women and Men' there are no drums, just cymbal." That's not a question, is it? Well, I guess... Well, it's about the music.

Michael Small:

You don't have to answer every single question. You can actually pick and choose things that you want to talk about. And go ahead and give the name of the person who's asking because that person likes a little recognition.

John Flansburgh:

Rosie98: "Do you think that your music has changed dramatically from the Flood album of 1991?" Well, the way we put our songs together in terms of the writing has not really changed at all. Basically we kind of, you know... work on different strategies to come up with songs. The end result is a little bit different because we have a full band. And in a lot of ways, I think it's more full-blown sound. It's sort of sonically more full blown. And the music comes out more, which is a big plus for us. Because for a long time, people really thought of us as strictly this lyric-driven thing, that we had interesting lyrics and that the songs were just kind of this background stuff. And one thing that's nice about having a good band backing us up and also um... while working with really exceptional players, um... we have a chance to really put the music right up there with the words and it's impossible to separate the two. That's how we really like it. We like it to be kind of a package.

Michael Small:

Do you miss the old days when it was just the two of you, and it was really easy to just show up and set up your keyboard and that was it?

John Flansburgh:

Well, I mean, it's easy to get nostalgic. It certainly was different. I realize now, in the fullness of time, how odd it must have seemed to a lot of people. I mean, we played in a lot of theaters as a duo. And I'm surprised that we felt so... it seems really brave to me now, that the two of us could feel confident about facing an audience of 2,000 people, two people on a stage. But I was young and brave. Now I'm older and more frightened.

Michael Small:

One other variant on that question, which is not only how has your music changed, but if you can think back to what you really wanted in like the mid-80s when you were starting and what you really want now, is there a difference like what you want out of your career, out of your life?

John Flansburgh:

Well, I mean, what I really wanted was a career. I just wanted to have a chance to play music. So it wasn't that complicated. In a way we kind of have to reinvent our goals now a little bit, even simply because we've accomplished a lot of things that we wanted to do. We were a local band in New York for like four years before we made a record. And once you've been in the band for a while and you haven't made a record, it's very easy to think like, "Well, maybe we never will make a record." A lot of the recordings that we did at the beginning of our career were really not so much to make demos but to kind of get some personal satisfaction out of all the effort we were putting into what we were doing. Because it was really unclear whether anybody was going to find us or support what we were doing.

Michael Small:

When you work with one person for that many years, is it like a marriage where you end up making rules that you stick with over the years and the rules keep changing?

John Flansburgh:

Well, we're lucky in that our collaboration is not set in the same way that a lot of other musical collaborations are set. It's not like one of us is the lyricist or one of us writes the music. Our roles are pretty wide open. And because of that, I think we both end up getting a lot out of it. If we're interested in pursuing some part of it, the other one is certainly open to that. So it's not as restricted as a lot of other collaborative relationships are and because we were kids together, it's probably a little uh... you know, our general impulses are a little more unified. We actually do get along on a personal level but also probably more importantly we get along on a on artistic level. A lot of people like each other but their ultimate artistic goals are really different. For John and I, there's this, you know... when we started, we had this very clear persona, like our agenda was very specific. I mean, we really wanted to do music that was completely like, fat free. No solos, no extra stuff. Nothing repeats. Just this really stripped down, very minimal kind of approach to songwriting. And we have loosened up over the years.

Michael Small:

Now it's, "More fat! More fat!"

John Flansburgh:

Yeah, we definitely, you know... we enjoy like songs having a little more room to breathe. We've also become a little bit more confident about what we're doing. It's interesting because our insecurities and our agenda were completely aligned at the beginning. You know, I think we were really afraid of boring people and we wanted to make this really pushy thing and, um, over the years we've become a little more confident and that definitely gives us some more leeway.

Michael Small:

So let's go to another question from somebody listening.

John Flansburgh:

OK. "Will TMBG come to Toronto soon?" I do not know. Somebody, OB. "Have you ever seen Return to Oz?" Don't even know what that is. "What do you think is your strongest album?" Well, for me our first album is our strongest album just because it's really uh... even though it's got this really kind of kaleidoscopic aspect to it and there's a lot of rhythms and different musical styles incorporated it's really of a piece and almost every song kind of uh... has its own special thing about it and everything is set really nicely and ever since then I mean especially with like Lincoln and Flood I feel like there's a big range of musical styles uh... it seems like more of a hodgepodge and uh...

Michael Small:

Do you have any favorite songs that you love playing?

John Flansburgh:

For years and years I loved playing "Don't Let's Start" believe it or not, even though we would basically have to play it at every show and still play it more at more shows than not. Because it was a great, it was not uh... it was just kinda by accident. It just has a lot of different guitar things in it... I get to play like chords and lead lines and you know the "duddle dee dah" part -- it's just really fun.

Michael Small:

Which one of you sings that?

John Flansburgh:

That's the other thing. Linnell sings it. So I don't have to do anything but play.

Michael Small:

Does he fun put on uh... a slight accent sometimes? Like, the Boston accent comes out a little bit more sometimes than others. Is that intentional?

John Flansburgh:

John is, um... there are songs that we sing that are in real character voices on records. But by and large in the shows I think we pretty much sing with what feels like our straight voice. A song like "Window" on the last record, you know John's voice is slowed down and he's singing in this mannered way but uh... "Don't Let's Start" is probably essentially his straight voice. I mean, singing is not as organic a thing as people think it is. You still have to make decisions about how you're going to sing. Or if you're not, not being self-aware doesn't mean that you're not still making decisions about something.

Michael Small:

What song do you love singing?

John Flansburgh:

I really love singing this "Pet Name" song, which is a new song on Factory Showroom. Basically just because it's got a pretty big range and I get to sing in a really full voice.

Michael Small:

The last time we saw you in San Francisco, you were very athletic on stage. There was a lot going on. It was a real show. Now, is it the same for this tour?

John Flansburgh:

There's a fair amount of jumping around. Yeah, it's pretty much a physical show.

Michael Small:

Is that... partly staged? Do you have people saying, "Look it's getting boring here. Do something." And then at certain points in the concert you know to do something?

John Flansburgh:

Wow. It would be interesting if... nobody ever gives us that kind of feedback even ever.

Michael Small:

Wait all after the show today!

John Flansburgh:

Right. It'd be interesting if... we've always been very audience-oriented in terms of how we pace our show. We don't really want it to ever slow down too much... We do so many shows that I think there's a certain kind of wind tunnel testing that's been going on for a long time, that we know not to do things like put two slow songs next to each other or something like that. I'm constantly giving tedious show business advice to my fellow performers about what's a good way to put on a show and what's a bad way.

Michael Small:

Now we're seeing here that we can highlight certain questions if we want to answer them. So let's go back and answer another question from someone who's listening.

John Flansburgh:

Okay. Let's see.

Michael Small:

Do you want control of the mouse? I'll just pass this along.

John Flansburgh:

Well, what does the highlighting do exactly?

Michael Small:

He's an old hand at this.

John Flansburgh:

Okay.

Michael Small:

John told me before we started that he was just recently at SpinOnline.

John Flansburgh:

And the SonicNet. I've done the SonicNet thing twice now.

Michael Small:

But those you had to type, you didn't actually talk.

John Flansburgh:

Yeah, it was different. It's nicer to talk. So, "Ask if they ever get weird letters from fans. I mean, I skipped my high school homecoming last month. I was on homecoming court, and I went to their show in East Lansing. Does that, oops, does that make you..." Oh, okay. Uh... yes we get many weird letters from fans.

Michael Small

Can you remember a recent one?

John Flansburgh:

A lot of them are very sweet. A lot of them are from very young people uh... you know asking us to do things like you know come to their school you know and play or like take them to their high school dance or their junior high school dance or whatever. Here's one: "We'd like to know what the circumstances were at the Salt Lake City show when TMBG could not play the two encores they had on the set list." Well, I'll tell you what happened. We were playing at the show in Salt Lake. And I was walking off the stage, and there's these things called genies, which are what lighting rigs are set up on. They're basically just like giant tripods. And normally, when you're doing a professionally rigged show, there's big pieces of yellow tape all around them that say, "Stay away." Because they're these three-foot-long metal rods running along the ground that are basically just like five or six inches off the ground for a distance of say three feet. And so they'll mark them off so you can't trip over them. And I actually, well, I wasn't the only one. Our bass player fell over one on the other side of the stage and the guitar player in Cub, our opening band, had also previously injured herself on the very same thing because they were completely unmarked and in total darkness. So I hit this thing and fell over and fell on both knees and basically thought, you know, I was just like paralyzed in pain. And my first thought was, "Well, the tour is over, but at least I can go home." So we didn't get to play because I couldn't even stand. But I'm better now, and that was only like a couple of days ago. So I'm kind of glad, because it could have been much worse. I thought I had broken something. "Will you be back in Toronto soon?" I don't think so. "What do you think is your strongest album?" Well, I don't know. I guess I said it already, our first. This record's pretty good. This record is, I think, is more dynamic than our last record. "Are both of the Johns going to be here?" No, John Linnell is eating dinner right now. How about some more questions, folks?

Michael Small:

Well, we have more questions here. Let's talk a little bit about the Internet. Do you go on and surf around and look at different sites at all?

John Flansburgh:

No I don't. I've been involved with putting together our website at... www.tmbg.com and uh... trying to just figure out how that would work best. By and large no. I do a lot of things with the computer with music programming and stuff like that.

Michael Small

What kind of computer do you have?

John Flansburgh:

I've got a 2CI, and I've got a Duo portable one. But in general, I feel like it's sort of like taking up smoking or something, you know? I know I'd really like it, and I'd probably be completely hooked on it. But I feel like the longer I can resist, the better person I'll be.

Michael Small

What about your songwriting techniques? Do you use the computer to write the music? Do you save all your ideas for the lyrics on a computer?

John Flansburgh:

Yeah. Actually, there's a lot of different ways in which we've used the computer over the years. And basically, we started with using drum machines very early on. And when MIDI and sampling came along, it was really a big part of our sound. I mean, there's a lot of personal sampling that we kind of explored on Flood and Apollo 18. And a lot of the songs are almost inspired by the sounds that we were getting. You hear something, you create a sound synthetically that just has this incredible quality to it. Like the song, "Snail Shell," the guitar sound, that kind of like weird power chord. It's like a fifth being played. It was kind of inspired by this electric guitar synth patch that comes with this Roland MIDI module. And what's funny about it is, it's really over the top. It's like it's got this, it's one of those sounds that's like, they put in the module to impress people in music stores because it's got this, WOW! Crazy! Uh... you know just sounds like Yngwie Malmsteen blasting off.

Michael Small:

I'd want to get some idea of how you actually produced so much material. It seems as if the two of your incredibly prolific. Does your day include -- every single day -- some writing down of lyrics some writing of music? Or do you go through periods where you do that for two months straight and then you stop?

John Flansburgh:

For me, the touring, the interruption of touring is probably a good way for me to feel like I don't have to write. We basically have a hard time writing while we're on the road. And I don't even know if we could, if we were just left at home without any stimuli, if we really would produce any more than we do now. Basically, I guess, we've recorded like a 120 songs or so and probably have, I don't know... I don't feel like we're that prolific actually, to be perfectly honest.

Michael Small:

Well what about Dial-A-Song? Is there really a new song on that every hour, or is that a joke?

John Flansburgh:

Well, it changes every hour and there's a big backlog of songs. Actually I'm just about to dump a bunch of other new songs on there as soon as i get back home. I sort of feel uncomfortable making too much of the prolific thing because I feel like it's not really that key. I don't think it necessarily, it doesn't really say that much about the quality of what you do in a way. I would rather write one song that people found, you know, really valuable and important to them than write a million songs that are just, you know, kind of, I don't want to get caught up in like this sort of like, he-man songwriting contest, you know, "I've written one million songs. I've written two million songs."

Michael Small:

I just imagine the two of you sort of like, it seems like this really creative life where you get up in the morning and you have this idea and you write a song.

John Flansburgh:

Well, it is great. I mean, I didn't write songs until I was about 20-years-old. It's a great thing to be involved in. I find it incredibly exciting. The best comparison I feel like I can make is like, I don't know if you ever worked in photography or have done anything in the dark room and you expose the photographic paper, then you put it in the developer. Then you go like... it's your photograph. I mean, you took the photograph, you're developing it. It's totally your thing. But there's also this element of magical, technical... when it comes together and you see it just kind of happen, it definitely feels like, you feel like there's another thing going on besides what you're doing. I mean, I've written a lot of songs. But I still get this kind of crazy excitement from the process of writing it when it actually sounds like a song, you know. There's an otherness to it that's hard to, it's hard to ever get used to for me.

Michael Small:

Do you write a lot of songs while you've got instruments there or do you write them in your head and then mark down musical notes?

John Flansburgh:

One thing that probably has helped us write a lot of songs is that we try to come up with a lot of different strategies to write songs, like, you know, write a song on an instrument that you're not familiar with. Over the years, I've tried a lot of different things. I've tried to write songs where none of the words rhyme. I've tried to write songs that only have, like, I wrote this song called "Moving to the Sun." I was trying to write a song that only had one chord. Use one chord and write a song, which is almost impossible thing to do, and chances are it won't be a good song. But it seemed like an interesting idea. When I put out the Mono Puff record, Rykodisc was kind enough send me this enormous pile of Elvis Costello reissues that they had put out. And I was going through them and looking at the liner notes and thinking about, you know... I mean there are all these written liner notes that explain about all these songs that he wrote. And I'm a big Elvis fan and I saw like there's this one B-side or something, bonus track that was on there. And he was saying, "This is a song I tried to write using one chord." And I'm like, "Oh God. You know, I'm not the only one." In a way, you're always just trying to find another sort of excuse to write another song.

Michael Small:

Have you ever thought of trying to just write a hit and make a lot of money, like write it even for somebody else? Because I feel as if you have all the elements to do that and that you've written songs that sound like hits to me. But have you ever thought, "Hmm, if we had only done that a little differently, we could have been number one?"

John Flansburgh:

Well, we're trying to write songs that will be interesting to people, as interesting as they can possibly be. And I guess part of it is that... there's limits to how self-conscious you can be when you're actually writing something or just involved in a creative act. I do have kind of a respect for people who are like... I'm trying to think of that lyricist who wrote the lyrics to a million billion hit songs... Sammy Khan, who just has the most crass "we're writing hits, baby" perspective on it. But some of his lyrics are like really poignant. I mean, he's not a hack at all. But he is thinking about how to tap into people, into an audience. How to speak to an audience. How to figure out what everybody's thinking about. Chuck Berry is the same way. When people ask him, "Why did you write that song about cruising along in your automobile?" And it's like, "Well, because all the teenagers have automobiles." I sincerely think he actually was thinking, "Well, what do most people want to do? What are most people into?" For me, it's just not that interesting to think about. I don't think about what most people do. Those ideas aren't very compelling to me. I guess I'm just not a populist. I feel like there's a generosity of spirit about They Might Be Giants that's obvious to a lot of people. But on some level it is a very personal expression. I don't think it's appropriate for us to like be thinking about what's on other people's minds.

Michael Small:

But did you or John ever write a song that you thought after you had recorded it, "This will be a hit"?

John Flansburgh:

No. I wish, you know, it would be really cool. At this juncture in my life, we're doing all the things that people with musical careers do anyway. I mean, we do interviews and tour and basically it seems like if we had a hit, the only thing that would change is it would make our lives a lot easier. I guess, you know, we run the risk of alienating people in our audience. But at the same time I feel like we've done enough work that people would realize that there is some kind of... I don't know. You can't just declare yourself... You know who I'd really want to talk to? I'd really want to talk to Randy Newman. Because he's somebody who had this incredible musical career that I completely respect. He wrote these very personal songs that are very inspiring to me just as kinds of songs. He wrote these extreme character songs. And then he had this huge hit that really in a lot of ways, if you hadn't heard it a million times, would just be like a lot of other Randy Newman songs. I mean, "Short People" is not that different than a lot of other... you know, it's like it works on a couple of different levels. It's a song that's essentially about intolerance or racism. And then there's this sort of obvious thing that's just kind of light and fun. But obviously it changed his career. He probably just got totally rich and things were really groovy for him afterwards.

Michael Small:

I remember when I was talking to Joni Mitchell about Dog Eat Dog way back, and she told me that she felt all the songs that she had written had the potential to be hits, and she was just...

John Flansburgh:

Right. But she had a lot of hits that were completely like herself. I mean, you're sort of talking about... You're saying, like, "Do you ever think that if you changed an element of what you're doing, then you could have a huge hit?"

Michael Small:

Yes.

John Flansburgh:

I mean, it's hard enough to even come up with the original thing, let alone, like, try to figure out how to dismantle it to make it safe for mass consumption. I mean, we edit ourselves pretty severely and we critique ourselves pretty honestly a lot of the time. We definitely know that some of the stuff we do is stronger than others. But for Joni Mitchell, it's probably very confusing. Because she does a lot of songs that are really... a lot of her biggest hits are these really idiosyncratic crazy sons that are just pure expressions of her musical thing and, you know, I would imagine that it probably is true. She'd probably go, "If Yellow Taxi can be hit, why can't this one be a hit?" And she's right!

Michael Small:

There's another thing before we go back and see if there are more questions. I'm just curious again about the things you've seen change since you started your career. In an odd way, even though the political situation was worse in the 80s, I felt that the art scene was pretty exciting when you were getting going and you were part of this sort of excitement that things were going to change and something new. And I have a sort of creepy feeling about the 90s and I can't put my finger on it. I'm wondering if you have any sort of feeling about the times we're in, like what worries you or what excites you right now? Do you feel good about where the world is at?

John Flansburgh:

I sometimes wonder if, personally, if just rock music as like a form of like, uh, kind of subcultural expression is actually... over. It seems like it's in kind of, you know, this mannerist period where you can really easily point to almost any group's... what's at the core of their style and find some predecessor. There's a lot of stuff that's essentially retro. And that just seems kind of not good enough to me. There should be more original bands. There should be more bands where you go, "I don't know what kind of music that is. I don't understand that music." Most of what I hear sounds kind of like strange versions of things that I already knew really well. And I think there's a good chance that maybe it just is on its way to becoming some kind of museum piece. It would be nice if it was sort of parallel to like jazz right before bebop came along. But maybe that's what rap is. I mean, maybe rap is really the future of rock because it has a lot of the elements that... People are really intolerant of rap's message. People have a really hard time dealing with it in exactly the same way that they had a really hard time dealing with Little Richard or the Jefferson Airplane or any band that was just saying, "Be a total weirdo and step outside of society and join us on the other side." Maybe it's certainly not, I'm not gonna start... I don't think I will be an Original Gangsta too soon. But I think in some ways that it's hard to ignore the fact that most rock music is just essentially a known quantity. And it seems like it might really be over. The other thing that strikes me a lot of times is that with the Internet as sort of a fad that's coming up, and it obviously is really a big part of teenagers' lives, it seems like it's just another way to get to countercultural things a lot sooner than going to the mall and finding the weirdest record you can find in the mall. Which was for me, like that was my window, you know, finding like a Captain Beefheart record or a Frank Zappa record at the Burlington Mall in Burlington, Massachusetts. That was like a great, you know, that was a tremendous window on to other kinds of music. And you know, it definitely helped. To some extent, it's an interesting question, you know, what people have access to definitely affects the way they... approach the culture.

Michael Small:

Because there are the more cynical people who would say, "Yes, this is the hype that we're told that the Internet is going to make counterculture more accessible. But in fact it's not really working that way." Would be the cynical viewpoint.

John Flansburgh:

Yeah, I think, obviously there's more stuff, you know... people have access to more outlets. I guess just as a suburban kid, I felt very isolated. And when I got to go into the city, it was fascinating. And I feel like in a lot of ways, the Internet provides people with a similar kind of experience. I was listening to NPR, and they were having a discussion with book retailers. And they're talking about all these Borders and Barnes and Noble stores opening up with coffee shops in them. And there are book clubs. And there are all these different kind of... how mall culture is becoming more sophisticated. And there's sort of a teen aspect to it. This kind of bohemian... there's sort of a miniature teen bohemian thing happening in all these mall chain bookstores. And basically I was listening to all these New Yorkers who feel like their whole personal identity is defined by the fact that they moved out of their small town, moved to New York, became a sophisticated person and told their friends and parents, "No, I'm different, I'm an individual, I'm an intellectual, I'm going to make a stand in this culture." And they basically just can't get over the fact that a lot of people would be into it if given the opportunity. And there is something very elitist about, I mean, it's sort of in the nature of Bohemia or in the nature of counterculture. It is an elitist act. If everybody's invited, then how could it be good?

Michael Small:

And how do you answer that question?

John Flansburgh:

Uh... get over it. We're here.

Michael Small;

Are there more questions on the screen?

John Flansburgh:

Oh, there are many. "Did Johnny Cash ever recognize or even hear his sample on the Pink Album?" We sample the Johnny Cash record on our first album and uh... actually the first time we ever met with the lawyer, we had a long list of questions for him because we didn't know like about the legality of certain things, and one of them was about clearing the sample of Johnny Cash and uh... it was like twelfth on the list of you know fifteen questions and we asked him the sixth question and our lawyer said, "Well that's an interesting question. Because I was representing Johnny Cash once, and we sued the pants off this guy and made a ton of money off something." And we just skipped over the the 12th question. And no, we never talked to him about it. I don't think he's ever heard it.

Michael Small:

What was the sample?

John Flansburgh:

It's him saying, "Mama sang bass."

Michael Small:

Oh, right. Sure. I thought it was you imitating him.

John Flansburgh:

It's from a really sort of bad Johnny Cash song, actually.

Michael Small:

Yeah, I thought you were doing an impression of him.

John Flansburgh:

No, no, it's a sample. It's actually one of our earliest samples. "I heard that there will be a new B-side compilation. Is it true?" Yes, in February we're coming out with a two CD set that basically compiles our first album, the album Lincoln, the EP record Miscellaneous Tea, and then there'll be about 15 unreleased songs from around 1985-86 that will all be on two big CDs. There'll be like 80 songs on two records, and that'll be out in February. It's called Then -- The Earlier Years, and it will be on Restless. "Is there any word about a new video?" It turns out that on "S-E-X-X-Y" might be becoming a big hit in Australia and uh... we might make a video for the... it's sort of confusing because we set out on this tour making a video and um... we've been working so hard at doing all these live shows. We opened for Hootie and the Blowfish for a month and uh... that was sort of right at the time that we would normally be kind of prepping for a tour. So we didn't get a chance to do a video, but now that "S-E-X-X-Y" is kind of taking off, it seems like we might be doing a video for that or we might be doing a video for "Till My Head Falls Off" which is probably the next single. Which is also answering another question from Mister Claw 2 -- all these names are unpronounceable. "What are your literary guideposts? What authors do you read?"

Michael Small:

Do you have time to read while you're on tour?

John Flansburgh:

I read a lot of biographies. And I don't read that much literature. I feel like I wish I did. I read this interesting book of poetry by this guy I was telling you about, Hal Sirowitz, called "Mother Said." And I just bought this book about making movies called "Hello, He Lied" by this woman who's a movie producer. I wish I actually read more literature but I feel like I never have enough time to really into it all the way. I read this great biography called Lush Life about Billy Strayhorn, Duke Ellington's collaborator. It was really a fascinating book.

Michael Small:

Did you read that Oscar Wilde biography? It was incredible. It's very large so it might not be easy for carrying around on tour. You really get into his whole life and learn a lot about the time.

John Flansburgh:

It's funny because people ask us a lot of questions about our work and about ourselves and our personal relationship to our work. A lot of times I basically feel like just saying, "Well you know it's just our work. Our personas are not that big a part of it." But then on the other hand I'm really fascinated by people's stories. So I understand the natural impulse.

Michael Small:

Can I ask a few of the biographical questions? Are you still based in Brooklyn?

John Flansburgh:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

Really? And you're married now, is that right?

John Flansburgh:

Yeah, I just got married this summer.

Michael Small:

Me too. Really? Congratulations.

John Flansburgh:

Congratulations to you. Was it a big ceremony, small ceremony?

Michael Small:

It was very small in Mill Valley, California backyard. How about you?

John Flansburgh:

It was in Brooklyn at the Botanical Gardens. It was quite nice.

Michael Small:

Oh, great. Relatively small.

John Flansburgh:

So when you say small, how many people?

Michael Small:

Oh, well, it got bigger and bigger. I think it became 80.

John Flansburgh:

It's still pretty small. 80 sounds like a big to people who haven't gotten married, but 80 is actually pretty, really keeping it under control.

Michael Small:

I know we did horrible things because we had a space problem so we told certain people, "You can't bring your girlfriend, you can't bring your boyfriend."

John Flansburgh:

Wow, bummer.

Michael Small:

I know, afterwards we felt terrible. We apologize publicly to all those people.

John Flansburgh:

Yeah, it is hard. I mean, we've had like 150 people, which seems like more than enough on paper, I mean, like just abstractly. But then when we actually realized that it meant 25 friends and their, you know... your parents, her parents, and our friends. It's not that many people.

Michael Small:

There's a building in the Botanic Gardens, right? Yeah, yeah, there's a whole set up there.

Michael Small:

And is your wife a musician?

John Flansburgh:

She is a musician, yes. And she's also a writer and is involved in all sorts of different like creative things.

Michael Small:

When you hold a wedding and now that you are famous, do people try to crash the wedding and things like that?

John Flansburgh:

No, no.

Michael Small:

You never know in this world.

John Flansburgh:

No, thank God they don't.

Michael Small:

More questions.

John Flansburgh:

So let's see. "How do you explain your long-lasting popularity through totally different periods, e.g. early and late 90s?" Hmm. Well, you know, I think we just have always kind of done the thing that we do. One of the nice things about being a band that isn't hooked into fashion or trends is that it's kind of like taking the low road. I mean you basically can hang out for a lot longer. Part of it is just we enjoy what we do and the other part is we've had a great, very loyal audience. I mean I'm constantly amazed at how much people respond to what we do. I mean, they really are very cool about...

Michael Small:

My mind is wandering off towards the question about what books you read. Is there something else that, like, when you have time to do whatever you want, you're on the road, what would you do? Do you play video games? Do you watch TV? Is there a TV show you love watching? Do you like going to Star Trek movies?

John Flansburgh:

I like going to junk stores. I really like being in the debris of the first half of the century.

Michael Small:

I could find some debris for you and send it your way.

John Flansburgh:

It's funny. It's not so much that I want to... I don't really collect anything. I collect some old magazines. But by and large I actually really enjoy just being in that setting. I'm just kind of sifting through books and old records and things... kind of the... you know, what's left over.

Michael Small:

What are the old magazines that you treasure? Do you have a particular one that you love?

John Flansburgh:

No, I mean, just magazines that are about popular song magazines, or even just like, you know, on a pretty regular basis, I'll just buy a Time magazine from 1932, and I'll read it at lunch. And it's just a really interesting way to experience history... it's not somebody telling you what's important. It's just really informative. It's an interesting window on people's points of view from that time.

Michael Small:

Yeah, the perspective. Are there examples of things that you've read that really shocked you and seemed totally different from the way you saw it in history books?

John Flansburgh:

Well, gender roles are certainly more established. People made a lot of assumptions about what women were good for and what men were good for. That's probably the most shocking thing, because that's really up front. But I guess I'm just really curious about the history of this century.

Michael Small:

Well, maybe we should take a few more questions, and then we'll wrap up with a few more.

John Flansburgh:

OK, here's the speed round of questions. "How did you get those neat necklaces that you had on Conan?" Well, they were made by our graphic designer Barbara Glauber who designed the cover of our most recent record and did the MonoPuff record as well. They were made by hand and they are not available anywhere. "When will the Larry Sanders show air?" It's airing tonight and you should check it out. I think it's on at like 10 o'clock. In the middle of our show. But if you're not in San Francisco, I would say check out HBO. "Was the Hootie and Blowfish tour a record company idea or your own?" Actually, it was the Blowfish's idea. They called us up. They're big fans of the band and asked if we were interested in doing it and they offered us some dough. It was sort of an experiment. Basically, we knew exactly what we're getting into. I think people are always surprised. They go like, "Why you know why would you go do that?" But for us it was a way to get... we played Nebraska in front of 20,000 people. We're never going to be able to do that otherwise.

Michael Small:

How was it being an opening act?

John Flansburgh:

I don't like being an opening act ever. I opened for Elvis Costello last year and it feels like work. If we weren't doing a real tour afterwards, I don't think I'd be interested in doing it. It's a very unsatisfying thing, because you're basically playing for a cold audience and even if you win them over with a song you're just as likely to lose them on the next one -- especially doing the kind of material that we do. We've had some good experiences doing festivals where we're playing for really diverse audiences and audiences that definitely aren't there to see us. So it was a way to open up our audience.

Michael Small:

Were the Hootie people polite?

John Flansburgh:

Oh God, they're so nice it's crazy.

Michael Small:

I mean, the audience.

John Flansburgh:

There were a couple of shows where people were chanting "Hootie!" But our audience chants "Giants! Giants!" at our openers. You know, people have this conception that the opener is in the way of the headliner a lot of times. They don't realize that schedules are made weeks in advance and shows are run in union halls. There's so many more rules about putting on a show than people ever would know.

Michael Small:

When they chant "Hootie! Hootie!" do you go back into the dressing room and throw yourself down on the sofa and sob?

John Flansburgh:

I was just happy if we could get off stage before they turned the house lights on. That was the thing that was the most jarring. It would be like... you know, running across the Enormodome's floor in the back, you know, like the stage is sort of at one end of like the arena, and then there's this sports complex. Then there's kind of a long walk to where the backstage area is. So you're still inside this sort of performance area, and every other show, we wouldn't actually make it to the door before all the house lights came on. It was just this bright fluorescently lit room. Just kind of took a lot of the mystique away. But anyway, enough about that. "What do you think is the main priority and strength of your group now, the lyrics or the music?" Well, I think we basically try to do a unified thing. I mean, we really think of it as songwriting. And sometimes a really slight lyric can be supported by a really bold and interesting piece of music. And sometimes, like a...

Michael Small:

Sometimes nothing will support those slight lyrics.

John Flansburgh:

Sometimes nothing will help. But... I don't know. Basically, it's a package deal. That's how it always is for us. "Where do you come up with the idea for Particle Man? What, if anything, do you mean by it?" Well, that's a question really for Mr. Linnell. But we get asked that question a lot. The main thing is that people are wondering if it's a metaphor for something else, which I think it's safe to say it is not. It's basically just a character song. It describes a set of relationships between these different characters that are, you know, kind of... there's a theater to the song that I think is kind of interesting.

Michael Small:

Is "Little Bird House in Your Soul," is that really about a nightlight?

John Flansburgh:

Uh huh.

Michael Small:

Just checking. Next.

John Flansburgh:

Okay. Do people ever call and order the truck in The Old Fire from 94? Our manager actually... uh... collects cars and uh... we've offered one of them up for sale for basically the press to be willing to sell it for... I don't know if you got any offers on it. The idea was that basically it would be like... we sell a lot of t-shirts and things with the name They Might Be Giants on it. So we would sell you this. It was a Morris Mini Minor pickup truck. It's about the most adorable vehicle you've ever seen. It's like strange -- it's tiny but it's a pickup truck. Got this tiny little back on it and uh... but nobody's bought it.

Michael Small:

But it ain't cheap.

John Flansburgh:

Well, he got it for a song. I don't think he was too deep into it. Well, that's all the questions I've got here.

Michael Small:

Well, the wrap-up that I want to do is just to ask you about the things you have planned for the future. First of all, are you going to be directing any videos?

John Flansburgh:

I probably will direct a video in January. I've got to talk to my rep about it while I'm in Los Angeles.

Michael Small:

So you can't reveal the name of the band or anything like that?

John Flansburgh:

Oh, I don't think they even know that they're making it yet. Yeah, I mean, the whole video business is basically founded on the idea that it's already late in the day, and we've got to get going because we're way behind schedule. I mean, I've worked on a lot of videos, and they're almost all... there's no planning involved. Like, you get the job, and you're working on it. It's like done three weeks later. It's crazy.

Michael Small:

And is there an end plan to this tour or is it just sort of indefinitely continuing?

John Flansburgh:

We're on the road until Christmas in the United States. Basically we're going to be playing all over the United States until then. And we're going to be doing Friday nights in New York City at Irving Plaza in February. We're actually writing new material for those shows. It's kind of like what we did last year, where over the course of the month, we'll be introducing more and more new material. And by the end of the month, we'll be probably playing almost an album's worth of new songs, which is a very exciting process for us. Then in March, we're going to Australia, Japan, and Europe. And in April and May, we're in the United States.

Michael Small:

Me too. So we have that in common.

John Flansburgh:

Yeah!

Michael Small:

So on that happy note, thank you so much for coming. We really appreciate it.

Lenny, HotWired:

All right. Thank you Michael. Our next scheduled live audio event on Friday: Laurie Anderson continues the Multimedia Pioneers lecture series presented by San Francisco State University's multimedia studies program. It's in talk.com Friday November 22 at 9 PM Pacific, Saturday at 0400 Greenwich Mean Time. You can find links to audio programs throughout the HotWired network on the audio files page. That's www.hotwired.com/audiolab/radio. Thanks to all who helped on today's show, including GB for the chat, Brian Benitez the engineer, Michael Small, and our guest, They Might Be Giants. Thanks for listening. Bye for now.

End of Transcript